When I first started reading The Paris Express, I had a strange feeling of deja vu. It wasn’t that I thought I’d read the book before. In fact I was a bit disoriented at first, wading through a lot of characters I didn’t know and who didn’t all fit together was a lot to take in. It was more that I had a sense of when I was. The books that immediately came to mind were Dubliners by James Joyce and Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf. Both books have passages on public transport, but it was the drifting quality of the writing and the ‘democratisation’ of people being pushed together in a small space. They are forced to exist together for the time of that journey and even though this Paris train has First, Second and even Third Class, there is such a mix of generations, classes and genders that there’s potential for desire, tension, friction and misunderstandings. However different they may seem, the fate of one of them, is the fate of all.

What Woolf achieved beautifully in Mrs Dalloway, is that experience of being in the same place and looking at the same thing, but seeing it completely differently. The much loved Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, works on the basis that two people can witness exactly the same event but view it differently. They experience the event through a filter of their own past, their general well-being and mood that day, even whether they’re in a rush or feeling hungry. Woolf shows us that a car backfiring in the street is just a car backfiring to some, they hear it, recognise it and file it away to be forgotten. Whereas, Mrs Dalloway who is slightly anxious and focused on getting things done for her dinner that evening, actually flinches against the noise and immediately her brain starts questioning what it might have been? She will remember it and possibly even comment later that she jumped out of her skin. Septimus Smith hears a bang and is immediately back in the trenches, surrounded by death and destruction. It might even send him over the edge. I felt like Emma Donoghue really achieved that feel here. We can hear the conversation in each carriage and even go into the minds of some of the train’s passengers, but each one is reacting differently to everything that’s going on. Gradually I was compelled to keep reading because the tension was rising with every new passenger and because the reader is omniscient. Donoghue gives her reader the full story and we know the potential fate of every one of them.

Set in 1895 on a train journey to Montparnasse, Donoghue places us within the fin de siecle, with every little detail. It isn’t just her description of the train, it’s the character’s clothing and their attitudes. One passenger muses on the very idea of the fin de siecle, debating whether the closing of a century does cause a decadence of behaviour and fear of the coming century. There’s certainly evidence of a shift in attitudes to the Victorian ideals that have held firm throughout the 19th Century. In one journey we can see women being more outspoken, having a definite sense of purpose, and a need to determine their own destiny. Women are travelling alone or for work, in the case of Alice she is travelling with her boss as the secretary for his photographic business, but she is enterprising. She takes the opportunity to talk to him about moving pictures, looking for permission to make a short film. She has researched the subject and thinks it could be a new market for the firm. Marcelle is researching in the field of science and huge fan of Marie Curie who is so work focused that she went to get married in an everyday blue dress and spent their gifted money on two bicycles so they could ride to the lab every day. Marcelle knows it isn’t just her gender that may hold her back, it’s her race: ‘a pair of twits in her anatomy class once asked her to settle a bet as to whether she was a quadroon or an octoroon.’

Blonska has a variety of skills, but she’s also incredibly perceptive and quickly reads the other passengers in her carriage. I was absolutely fascinated with Mado. She stands out more than she realises, with her androgynous clothing and short hair, not to mention the lunch bucket she’s clutching as if her life depends on it. She’s a feminist, an anarchist and like Blonska seems to have an interest in reading other people. Her own internal struggle is so vivid that I could feel the tension in her body as I read. She seems contemptuous of many of her fellow passengers, particularly the men, knowing that the Victorian feminine ideal is simply a role women are forced to play. To step outside of the norm is brave and a deliberate outward show of her inner strength and determination to change women’s place in the world.

‘That’s the price of wearing a tailored jacket with short, oiled-down hair. Even back in Paris, where quite a few young women go about à l’androgyne, sneers and jeers have come Mado’s way ever since she scraped together the cash to buy this outfit at a flea market last year. Her hair she cuts herself with the razor that was one of the few possessions her father had when he died. She’ll take sneers and jeers over lustful leers any day. Bad enough to have been born female, but she refuses to dress the part.’

Throughout the novel there were complex relationships and interesting vignettes, sometimes no more than a line that made me rethink the people I’d been journeying with. There’s a grandad who hops off the train at the last stop to have a furtive and erotic moment with a stranger. As we spend time with the train crew, I learned a lot about their working conditions – having to relieve themselves by hanging over the side of the engine. They struggle amongst the chaos to read tickets and make sure people are in the right carriage, some actually choosing to downgrade their journey for some peace and anonymity. I was faced with my own assumptions near the journey’s end as I learned something about two of them that turned their relation to each other upside down. Of course they’re not the only ones who are pretending to be something they’re not. The author takes us far beyond the beautiful period costumes and shows the reality of train travel – ladies having to relieve themselves in a handy receptacle while the men look away, the inconvenience of a heavy period on a long journey, the strange contents of some traveller’s picnic bags as duck legs and creamed leeks made an appearance! The birth scene brings home the indignities of bringing life into the world, especially in a small train carriage. It is Blonska and Mado who have to help the poor woman, who is desperately trying to convince her baby that now is not the time. Mado has experience with midwifery too:

“Nothing ever came of all that labour—no more little Pelletiers, nothing but stains on the floorboards. Ever weeping,Madame Pelletier blamed the devil. But Papa taught Mado that her mother’s losses and his own paralysis— such broken health among the hungry and worn out—could be no accident. Employers, politicians, and capitalists were to blame for the sufferings of the working classes.“

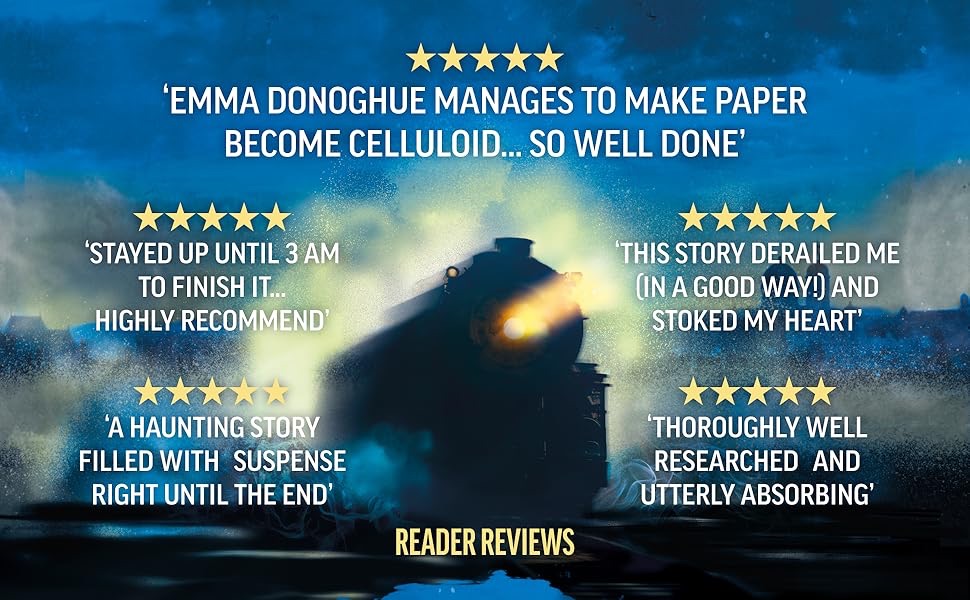

This was one of those novels that becomes much more than you expect at the beginning, although I should have known that since Donoghue has never let me down yet. I loved how she ended the novel and the journey because it was such a surprise, along with the afterword. I don’t read the blurb or reviews of a novel I’m about to read and come to it completely fresh, so I didn’t expect it and appreciated it all the more. Donoghue’s ability to see the unexpected, the downtrodden, the extraordinary and the silenced voices, of both a story and it’s place in time, is at it’s peak here. These anonymous and ordinary train carriages are made fascinating and unique by the character’s inside and their intentions. Through them she drives the story along faster and faster, until you simply have to go with it and read through to the end.

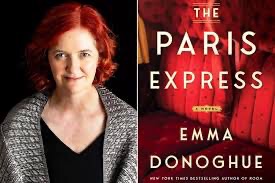

Meet the Author

Born in Dublin in 1969, Emma Donoghue is a writer of contemporary and historical fiction whose novels include the international bestseller “Room” (her screen adaptation was nominated for four Oscars), “Frog Music”, “Slammerkin,” “The Sealed Letter,” “Landing,” “Life Mask,” “Hood,” and “Stirfry.” Her story collections are “Astray”, “The Woman Who Gave Birth to Rabbits,” “Kissing the Witch,” and “Touchy Subjects.” She also writes literary history, and plays for stage and radio. She lives in London, Ontario, with her partner and their two children.

The Paris Express is out this week from Picador