The sky is clear, star-stamped and silvered by the waxing gibbous moon.

No planes have flown over the islands tonight; no bombs have fallen for over a year.

___________

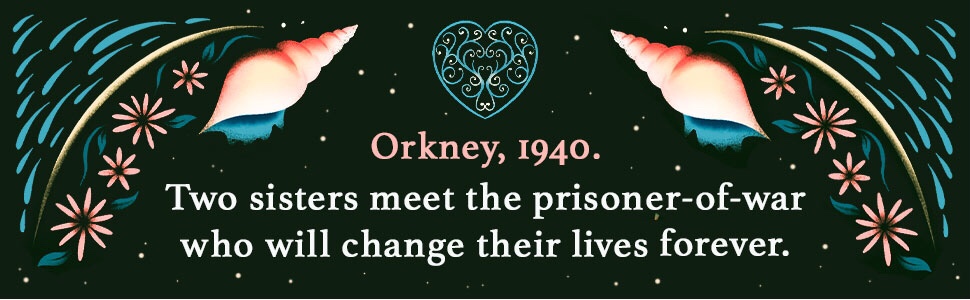

Orkney, 1940.

Five hundred Italian prisoners-of-war arrive to fortify these remote and windswept islands. Resentful islanders are fearful of the enemy in their midst, but not orphaned twin sisters Dorothy and Constance. Already outcasts, they volunteer to nurse all prisoners who are injured or fall sick. Soon Dorothy befriends Cesare, an artist swept up by the machine of war and almost broken by the horrors he has witnessed. She is entranced by his plan to build an Italian chapel from war scrap and sea debris, and something beautiful begins to blossom. But Con, scarred from a betrayal in her past, is afraid for her sister; she knows that people are not always what they seem.

Soon, trust frays between the islanders and outsiders, and between the sisters – their hearts torn by rival claims of duty and desire.

A storm is coming . . .

In the tradition of Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, The Metal Heart is a hauntingly rich Second World War love story about courage, freedom and the essence of what makes us human during the darkest of times.

This book is stunningly beautiful, so much so that I had to sit and think in the quiet when I’d finished it. It’s so rich in folklore, historical detail, the trauma of war and bereavement that I know I could pick it up to read again and still find something new. I immediately ordered a signed copy for my forever shelf, because it is so special. What did I love about it? The Scottish folklore, the incredible landscape, the community, the dignity of people facing the hardest times of their lives. Then amidst the chaos, violence and confinement, beauty emerges in the shape of a deep, immediate, connection and growing love between two people who can’t even speak the same language. The counterpart to this human story is the Italian Chapel, built out of the scraps of metal huts and concrete the prisoners are allowed. Yet from these humble materials a building of true beauty emerges, that still stands today. It made me emotional to think about the lovers, but also the patience and faith of these incredible men who needed a place to worship, a piece of home.

Dorothy and Constance live on Selkie Holm, a small island close to Orkney. They are isolated outcasts, strange simply because of their doubling, but also because they’re thought to have bad luck. There are myths about the island and the selkie women that might lure a man into the water. People go missing there and the old fishermen who gather in the tavern love to swap old stories about the strange shapes seen in the water. It’s said that if you live there you might go mad. Besides, the girls have had bad luck enough with the drowning of their parents as they tried to row to Kirkwall hospital in a storm. People mutter that it isn’t right for two young girls to live there alone. Surely they must need other people? Yet, that’s exactly what Con doesn’t need. They live in the bothy because of a traumatic event that happened in Kirkwall and now she’s frightened of people, particularly men. So when it’s announced at a town meeting that Italian prisoners will be housed on Selkie Holm, Con is terrified. Their protests fall on deaf ears, since the sinking of the Royal Elm, Churchill has decided barriers must be built to prevent invasion. The prisoners will build the barricades and soon there are huts and barbed wire and men with boots all in Con’s place of safety. Worst of all, Angus McLeod has been given a job as a guard on the island and the girls want to avoid him most of all.

This is a story about freedom for all three main characters. Of course Cesare is the one literally behind a wire fence, but Dot and Con’s bothy is a prison of their own making. Watching each of them try to inch towards freedom in their own ways is moving and upholds my belief as a therapist that everyone is capable of change and even in the most straitened circumstances we still have choices. Cesare finds freedom in the infirmary where he is cared for, in the Major’s office helping with correspondence, in the building of the beautiful chapel and the first time he sets eyes on Dorothy or Dorotea in Italian. His utter joy at finding something so precious amongst the dirt, the heavy labour, the biting wind and the regular beatings, is hopeful and bittersweet. Just like the unexpectedly beautiful chapel, treasures are often found in the dirt.

‘Up on the hill, the chapel gleams in the sun. I imagine the light pouring in through the window. The pictures on the walls will gleam with life. And, on the ceiling above the altar, a white dove soars through a bright blue sky. How does something so beautiful come from such darkness? The tears are flowing freely now, as I turn back to the people watching me and I force myself to say, ‘Thank you.’

‘‘Up on the hill, the chapel gleams in the sun. I imagine the light pouring in through the window. The pictures on the walls will gleam with life. And, on the ceiling above the altar, a white dove soars through a bright blue sky. How does something so beautiful come from such darkness? The tears are flowing freely now, as I turn back to the people watching me and I force myself to say, ‘Thank you.’Up on the hill, the chapel gleams in the sun. I imagine the light pouring in through the window. The pictures on the walls will gleam with life. And, on the ceiling above the altar, a white dove soars through a bright blue sky. How does something so beautiful come from such darkness? The tears are flowing freely now, as I turn back to the people watching me and I force myself to say, ‘Thank you.’

Dot finds her instant love for Cesare overwhelming, but she never questions or doubts her feelings or his. Con often reminds her what men are capable of, that she can’t trust someone she doesn’t know. Yet, for the first time, Dot places a boundary between herself and her sister, simply saying ‘I am not you’. This isn’t a criticism of her twin, but just an assertion that she is different, separate, and so is her life. She also makes a point of going to work in the infirmary, leaving Dot at the bothy. This is the first time where Con can see Dot moving into a life beyond her, their psychic or spiritual link can never be broken, but to wake up and live without her physical presence must be terrifying.

For Dot freedom means the ability to live a life separate from her sister’s, but also beyond the shadow of Angus McLeod. Dot’s trauma affected both girls and when she couldn’t go out, neither girl did. They have spent every day and night together since. This wasn’t Dot’s trauma, but she stopped living just the same. Now she dreams of sitting in the warmth of Italy, with Cesare and his family eating wonderful food. The image is a mile away from the dark, cold and stormy reality. Con sees the changes in Dot, and recognises she’s drifting away from her. Fiercely protective of her twin, it takes her a while to realise that in Cesare, Dot has found a man who is gentle and won’t hurt her. She knows she can’t hold her back, but it’s a huge wrench, like giving away part of herself when so much has been taken from her already. Watching Con’s realisations about her trauma and the potential for healing was one of the most moving parts of the novel.

The historical detail in the novel is incredible. Caroline Lea writes in her acknowledgments:

‘I wanted the love affair between my characters to be constrained by time and intensified by the precipitous and perilous nature of war, so I took many liberties with timings and action. This was a very conscious decision: I’m painfully aware of the difficulties in fictionalizing real historical events and people and selling them as ‘fact’, especially when this involves taking on the voices of ‘real’ people: I was very certain that I didn’t want to do that.’

This explains her decision to change certain things: some of the history and geography is changed; the construction of the barriers was started by Irish workers; the sinking of a ship by German u-boat features the Royal Elm, not the Royal Oak. Yet the chapel, situated on Lamb Holm, is still standing and can be visited. Even the metal heart truly exists, created by metal worker Giuseppe Palumbi for an Orcadian woman he fell in love with. He had to return home to his wife and family in Italy and left the heart behind. By doing this she has made sure that no one’s real life experiences are encroached upon. This is definitely a work of fiction, although the amount of research and love for her subject is clear to see. The descriptions of the islands are simply stunning and the relentless sea is mercurial; one moment soothing and the next a punishing, vengeful god. The inhabitants of the islands intrigued me too, in the way they slowly integrated with these prisoners of war. Even the two girls, shrouded in grief and superstition, are gently supported by this generous community. Now the chapel is part of this community’s history, with the metal heart at its centre. It shows us that light can shine into the darkest corners and choosing to love, despite the pain and grief, can be the bravest stand we can take.

‘All across Europe, bodies are falling from the sky or into the sea, or are being blown high into the air. Every explosion is a name. Every lost life is carved on someone else’s heart. Every death takes more than a single life. It takes memories and longing and hope. But not the love. The love remains’.

Published by Penguin, 29th April 2021.

Meet The Author

Caroline Lea grew up in Jersey and gained a First in English Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Warwick, where she now teaches on the Creative Writing degree. Her fiction and poetry have been shortlisted for the Bridport Prize, the Fish Short Story Competition and various flash fiction prizes. She currently lives in Warwick with her two young children and is writing her next novel. Her work often explores the pressure of small communities and fractured relationships, as well as the way our history shapes our beliefs and behaviour.