Hello all. Welcome to my February favourite reads. It’s been a busy reading month and thankfully I’ve been feeling less foggy and able to read a lot more. I’ve also found more balance in my reading so I’ve been able to read by choice a lot more too. These are the best ones I’ve read this month, a couple still have full reviews outstanding but I’ll tell you a little bit about why I enjoyed them so much.

This beautiful Pride and Prejudice inspired book is an absolute dream to read and felt like being back with old friends. I had always felt that Elizabeth Bennett underestimated her friend Charlotte Lucas and clearly she was a character whose possibilities played on author and comedian Rachel Parris’s mind too. Taken from the point Lizzie rejects Mr Collins’s proposal, the book takes in events from the rest of Austen’s romance and carries on beyond giving us glimpses into events we don’t get to see, such as the Darcy wedding at Pemberley. It’s told from Charlotte’s perspective but with letters from other characters and glimpses into Mr Collins’s past. These give us an insight into his manner and behaviour, while the letters give us a new slant on other characters too. I felt that Charlotte was pragmatic in her choice of husband and found ways to grow within it – sometimes in spite of Mr Collins and other times because of him, rather surprisingly. She has purpose, status and time to educate herself. Even Mr Collins has to admit she has blossomed, but when a spark is lit with a visitor to Rosings will Charlotte pursue the one thing she doesn’t have – romantic love and passion? I loved this and I’m sure many of you will too. It is pitch perfect, funny, sad and incredibly entertaining.

I have raved about Tracy Whitwell’s series following the adventures of Tanzy, actor and reluctant medium. This is the fifth and final instalment so I wanted to savour it. After her eventful trip to Iceland Tanz is back on home soil and soon makes her way back to her childhood home of Newcastle. Both she and her ‘little mam’ have been experiencing dreams about hangings, in Tanz’s case very alarming ones where she has a bag over her head and a noose round her neck. Her visions are powerful and are accompanied by sudden and torrential storms. Knowing she needs some help here, she asks Sheila to come and join her. They’re soon at the very spot where a travelling witch finder condemned several women to death by hanging. Even more alarming than usual, he seems to be able to see Tanz too, coming at her with his ‘pricker’ – the implement he uses to prod his prisoners to see if they bleed. This is toxic masculinity 17th Century style and Tanz is going to know her new Icelandic guides and all her power to defeat it. There’s the usual eccentric characters, including an Amazon woman dressed ‘like a Valkyrie’ who is also researching local history of witches and a ghostly lady called Mags who is full of mischief when it comes to putting men in their place. This is genuinely scary in parts and is based on historical research of the area. It was great to see Tanz back home again and with a case to solve, a love story to wrap up and a surprise that might determine her future, it’s a great finale to this funny and fierce series.

I’ve been able to catch up on some reading this month and I’ve been dying to get to the latest Kate Sawyer. She is now one of my ‘must buy’ authors and this novel just confirms her status on my shelves. Using the structure of family holidays, this book follows four generations of one family and the secrets they carry. Starting post-war with Betty who is at the seaside with her little girl Margaret and husband Jim, but Margaret doesn’t know the secret romance her mother had with the son of a local factory owner. Jim was a pragmatic choice and he’s a good husband despite the facial injuries and terrible memories he carries. Jim is doing well in his job and a few years later they visit the beach with his American colleagues and a teenage Margaret. There something happens that changes the course of this family. The author takes us through the 20th Century, showing how the changing world shapes the experiences of this family. From a beach on the east coast of England, we see holidays in Cornwall, then abroad as Maggie embraces the opportunities of a her husband’s job as a travelling buyer, and when her brother Tommy invests in and up and coming area of Europe. We see how changes in law and culture make some relationships and break others. The women in this novel are exceptionally well-written and the issues they face from infidelity, domestic violence, infertility and the consequences of a more permissive society opening the door for a more open generation than the one before. Throughout, this is a family that tries its hardest to stay together, even when some members are on the other side of the world. I love complex relationship dynamics so this was an absolute joy to read.

This incredible debut by Rachel Canwell deserves all the praise it’s receiving online. In fact she had a books signing at my local bookshop in Lincoln and had sold out within an hour! Her book is set in the south of Lincolnshire, in the fens and a family who live on the banks of the River Nene at Sutton Bridge. The new swing bridge allows them to visit the village and on the opposite bank a port is being built. Next to their home is a small hospital, readied by their father to serve port workers when everything is finished. One dark and disorienting night the family are woken by a rumbling sound and the splash of things hitting the water, but it’s only in the morning that the full devastation can be seen. The bank has collapsed underneath the new port, the family has lost their occupation and one of its sons, who drowned trying to rescue workers. We meet the three women who tell our story in the 1910s, Eleanor and her sister Lily are the last family members living in the house adjacent to the hospital – still empty and unused. Eleanor has fallen in love with John, the local blacksmith but can’t make plans because of her sister Lily. Lily will not leave the family house, in fact she rarely leaves her bedroom. The loss of her twin brother in the port disaster still affects her daily and she will not allow Eleanor to leave her alone in the house. Eleanor’s best friend Clara is married to their older brother Frank and they live in the village with their children. Clara is married to a bully and she sees one in Lily, who passive aggressively controls her sister. War is looming and as a prisoner of war camp is suggested for the old port site tensions within the community rise. With grief joining domestic violence, manipulation and alcohol issues this family is set for an explosive reckoning. I became so attached to these women and their family’s tragic history that I read it so quickly. I will go back and read it again though. Every element – character, setting, plot – is beautifully done and the historical background took me back to a time when my own grandparents would have been working the land and living next to the River Trent further North in the county. This is an excellent debut that had me absorbed completely.

This was an unexpectedly great crime novel set around an auction rooms in Glasgow, a venue where criminal elements mix with rich collectors and eccentric dealers. Rilke is pulled into a difficult situation after his friend Les finishes his prison sentence. When one of the Bowery Auctions regulars, the creepy and questionable Manderson, is killed on the premises it’s only 24 hours till their next auction. In fact Manderson has been stabbed in the eye with one of the antique hat pins they had out for the viewing afternoon. An Edwardian amethyst pin would have had to make its way through a huge hat and into a woman’s long, piled up hair, to keep it secure. Now it’s made its way through Manderson’s eye into his brain and it’s going to take a lot of strength to remove it. Knowing the police will be involved and that Bowery’s will be implicated, perhaps it would be better if it wasn’t obvious that he’s been killed with one of their auction lots. Things get worse when a gangster turns up at Bowery Auctions with Rilke’s mate Les in tow. Ray has a way with a razor and he focuses Rilke with a swipe to Les’s face. Rilke must now investigate who killed Manderson in just ten days or Les will pay the consequences. His investigations will take him to an old school where many ex-pupils have reported sexual abuse, to a brothel named after a questionable film and a girl called Chloe who may or may not be controlled by her boyfriend, Dickie Bird. Will he find the answers that will save Les? More to the point, are the answers to be found outside Glasgow or a lot closer to home? Glasgow is a city that doesn’t hide its darker quarters or episodes in its history and we see them here from pubs to brothels and a particularly creepy old school. The author brings in modern concerns around women using Only Fans and other internet sex work to make ends meet. Can it ever be a feminist thing? There are also issues around coercive control and manipulation, but as Rilke learns it’s easy to get the wrong end of the stick. There’s a familiar jaded feeling around these issues and a knowledge that no matter what’s brought to light, some people will always get away with it. This is a gritty thriller with a streak of humour and some fantastic characters. I’m looking forward to the rest of the series.

Finally this month I’m recommending this brilliant thriller from Tana French, the third in a series featuring ex- Chicago cop Cal and his new life in the small Irish village of Ardnakelty. This is such an atmospheric read that manages to feel isolated, but suffocating at the same time. Cal and his fiancée Lena, who was born here, try to keep out of any local gossip or feuding. However, when young teenager Rachel goes missing one night in a storm both Cal and his woodworking protoge Trey go looking for her. She’s found in the river, after setting out to meet her boyfriend Eugene Moynihan at the bridge. She appears to have drowned but Eugene claims not to have made the arrangement to meet in such terrible weather and when the autopsy comes back it reports that Rachel had swallowed anti-freeze. Is this an accident or suicide. Cal and Lena suspect foul play and with Lena being the last person to see Rachel, staying out of this might not be possible. When Cal appears to side with his neighbour Mart against the Moynihan family tensions rise and Tommy Moynihan, family patriarch, starts to show just how much of Ardnakelty he holds in his power. This is a complex mystery, with risky allegiances and terrible consequences. The Irish dialogue is so beautifully written and there are moments of laugh out loud humour to dispel the tension. This was an incredibly good thriller with plenty of twists and a fascinating central character too.

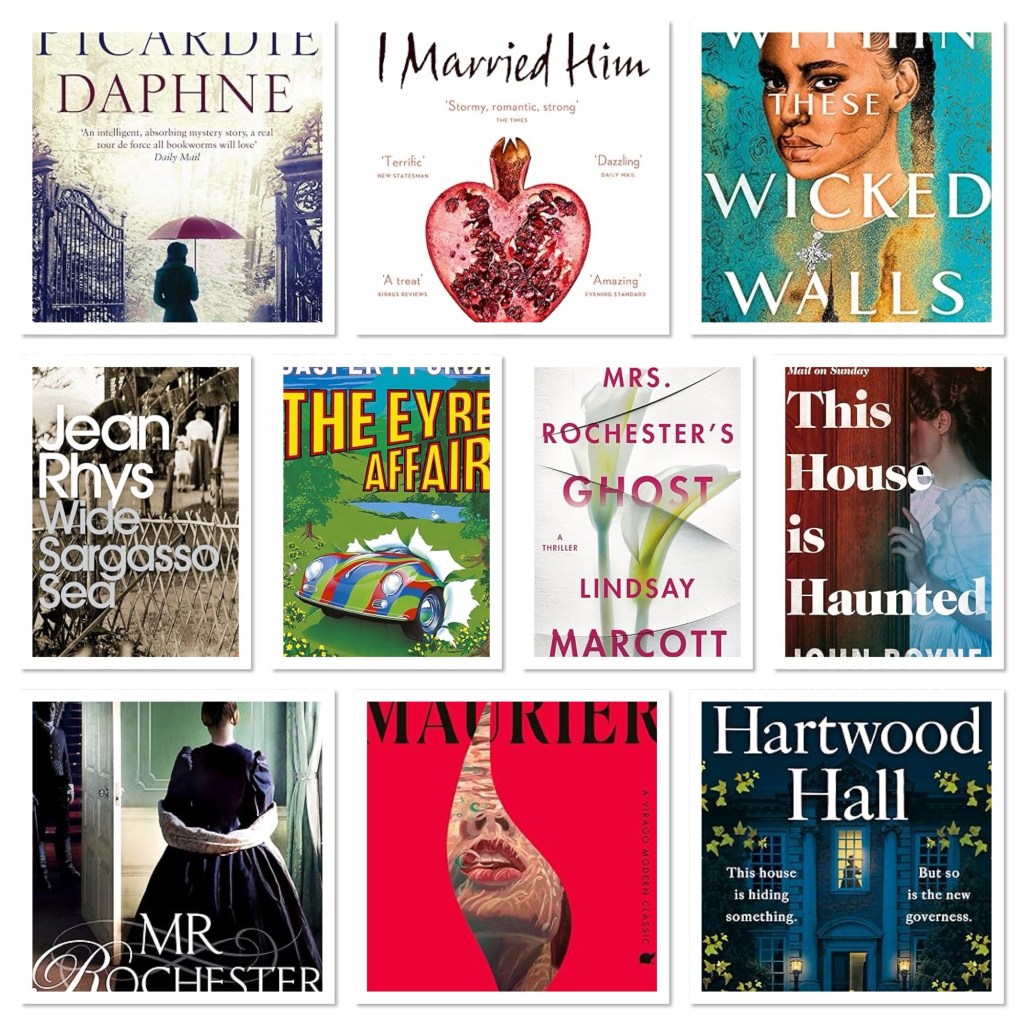

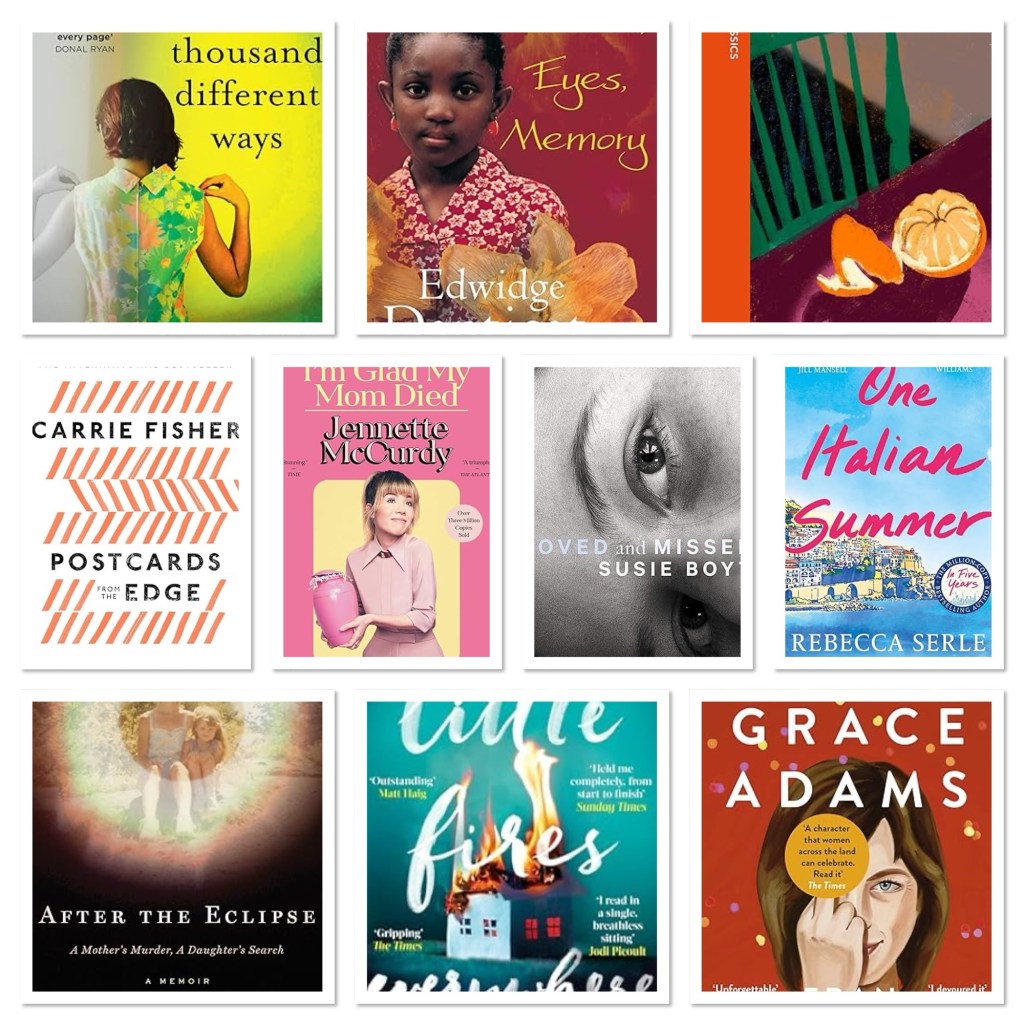

Here’s a selection from my March tbr: