Nova Scotia 1796. Cora, an orphan newly arrived from Jamaica, has never felt cold like this. In the depths of winter, everyone in her community huddles together in their homes to keep warm. So when she sees a shadow slipping through the trees, Cora thinks her eyes are deceiving her. Until she creeps out into the moonlight and finds the tracks in the snow.

Agnes is in hiding. On the run from her former life, she has learned what it takes to survive alone in the wilderness. But she can afford mistakes. When she first spies the young woman in the woods, she is afraid. Yet Cora is fearless, and their paths are destined to cross.

Deep among the cedars, Cora and Agnes find a fragile place of safety. But when Agnes’s past closes in, they are confronted with the dangerous price of freedom – and of love…

Eleanor Shearer tells stories about fictional people in situations I didn’t even know existed and then makes me root for them so hard that I cry real tears. Cora is our central character and we see everything through her eyes, so it’s no surprise I felt close to her. Cora is so vulnerable and thoughtful. She cares for her unusual ‘family’ – Leah who has brought her up and been a substitute mother and Silas and young Ben who’s still a young boy. It’s makeshift but it’s the only family she has known, ever since Leah found her as a baby. They are ‘maroons’, escaped slaves from Jamaica who settled in Nova Scotia, Canada. Many maroons negotiated peace treaties with the British, but part of that treaty forced them to aid the British in capturing any new runaways. However, Agnes’s freedom is more precarious. She’s out in the forest alone, except for her dog Patience, and it’s a harsh existence with the added fear of discovery. I’m not sure Cora fully understands that her presence and connection to the Maroons settlement adds to that anxiety and doubles her chance of discovery. Cora isn’t hardened to winter in the forest and hasn’t had to hone her survival instincts in the way Agnes has. Something she shows by getting into scrapes in the snow, saved by the ever present Patience. There are different types of freedom in terms of gender and sexuality too. Cora knows that Silas has an expectation that they will be together one day and so far she has avoided this. However, it is there in every confrontation they have; the fear of his resentment and the threat of sexual violence is ever present. Cora doesn’t question her sexuality, she just knows she loves Agnes. Will they have the freedom to be together?

The environment is an incredibly strong part of this story and here the author excels in creating a Nova Scotia that’s harsh but exceptionally beautiful. I found the time Cora spends in the forest incredibly peaceful to read, the animals, the ice and the frosted trees have a romance, a poetry about them. Yet she doesn’t hide the raw reality of living in it. The girls must trap animals, although Cora frees a white hare unable to kill such a beautiful and mystical creature however hungry they may be. One of my favourite scenes is when Agnes takes Cora out on a boat to visit the whales who appear for them as if by magic. As they sit among these huge creatures one of them lifts their head and looks directly at Agnes and she feels seen for the first time in her life. Not as a woman, or a slave, or a Maroon. Just as Cora, another living being. There are also moments where Mother Nature shows its bite and when Cora falls through the ice I was holding my breath. The suspense of those moments are brilliantly pitched and show us that Agnes’s lifestyle may have magical moments, but it can be lethal.

I love that Eleanor writes people back into history, we can read the historical facts about settled slaves in Canada but she brings their experiences to life in a way that hits the emotions and helps us to understand. We’re also reminded by Cora that women have choices, sometimes marriage is just another form of slavery. It’s something she’s keen to avoid, even if the offer came from a more loving and kind man like her friend Thursday. She knows herself enough to know it is not for her and she’s not willing to sacrifice herself. Luckily, Thursday is a loyal friend and will help Cora without imposing conditions. When Cora finds out the truth about where she comes from, secrets that have been held for years come flooding out and threaten everything that Cora has known about herself. When Agnes faces a similar reckoning it threatens everything in their future. I was emotional about the little details the author puts into her book such as the braiding of Cora’s hair being the only moment where they’re both present and the ‘love can flow between them unimpeded’. Cora’s loss of her sister also hangs over her and I loved the nature metaphors she uses to express those emotions:

“Cora cannot stop thinking of her life like a tree, with the branches that split and split again until you reach the highest […] that there’s somewhere, the branches not taken – the world where she stayed with Elsy and Elsy would still be living.”

However, in everything that happens, one loss hit me the hardest and actually brought me to tears. I loved the still moments created, where Cora learned to be in nature. Where they are both present and entirely in the moment. The fireflies are a symbol for Agnes and Cora, in that they are glowing in the darkest and coldest circumstances. Cora and Agnes have a bond that flourishes where many things don’t survive, they are extraordinary like fireflies in winter.

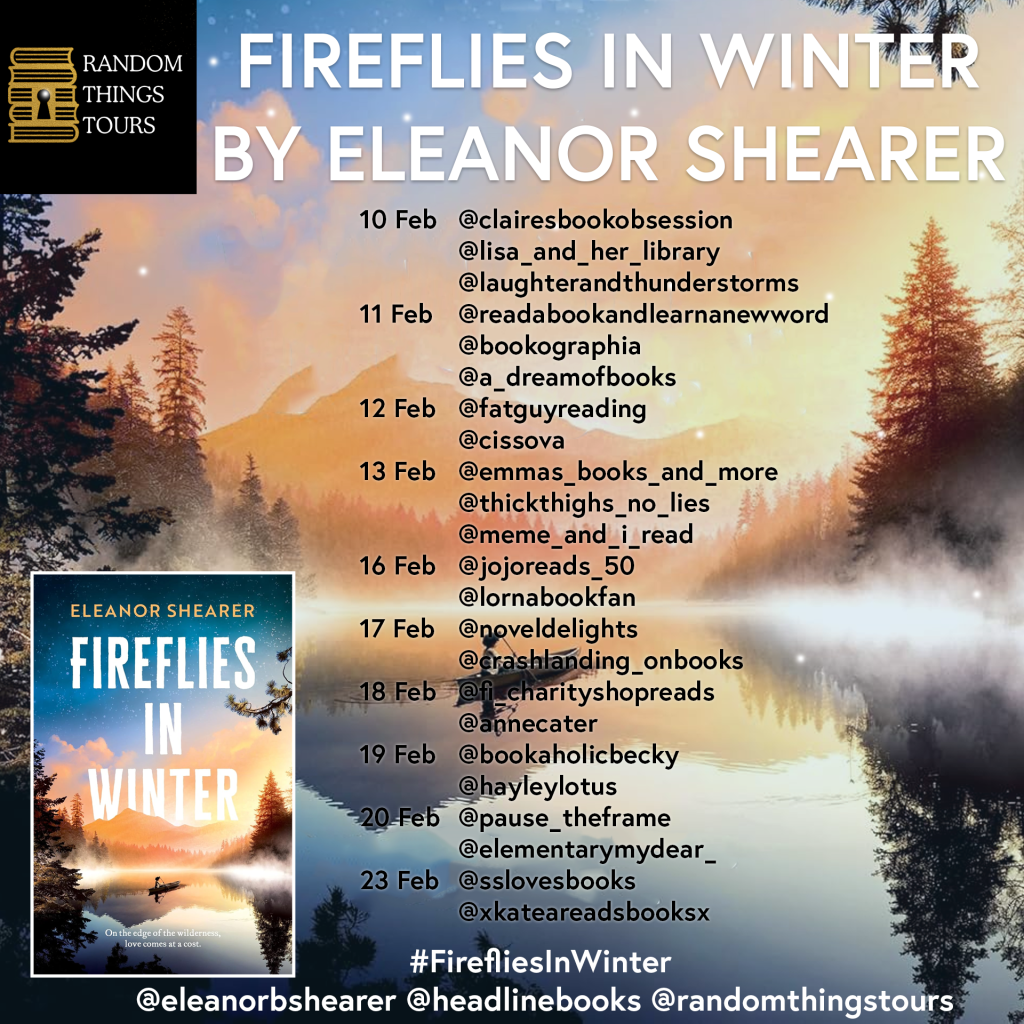

Out from Headline Review on 10th February

Meet the Author

Eleanor Shearer is a mixed race writer from the UK. She splits her time between London and Ramsgate on the coast of Kent, so that she never has to go too long without seeing the sea.

As the granddaughter of Caribbean immigrants who came to the UK as part of the Windrush Generation, Eleanor has always been drawn to Caribbean history. Her first novel, RIVER SING ME HOME (Headline, UK & Berkley, USA) is inspired by the true stories of the brave woman who went looking for their stolen children after the abolition of slavery in 1834. The novel draws on her time spent in the Caribbean, visiting family in St Lucia and Barbados. It was also informed by her Master’s degree in Politics, where she focused on how slavery is remembered on the islands today.

Her second novel, FIREFLIES IN WINTER, is a love story set in the snow-covered wilderness of Nova Scotia in the 1790s. When Cora, an orphan newly arrived from Jamaica, glimpses a strange figure in the forest, she is increasingly drawn into the frozen woods. She meets Agnes, who is on the run from her former life. As the two women grow closer, they learn more about love, survival and the price of freedom.