I’ve had a lovely reading month, with the subject of love and relationships being at the centre of most of my best reads in June. Possibly due to it being wedding season, romance seems to have been in the air and all my reads looked at it in a very different way. A couple are set in the present day but others range from the late 18th to the mid- 20th Century. Yet there was a sense of familiarity, with each book showing the difficulties in how women and men relate to each other and negotiate the rules of their relationship. Women seemed to wait an awful lot, trying to balance a career and a relationship not to mention children and home life. Some women were waiting for proposals, for a man to commit, to be faithful, or for life to begin. They bring up the age old question of women having it all and whether that’s ever possible. There’s also a lot of travel involved from the UK, to America, Italy, France, Switzerland, India and Australia. I hope you all have a great tbr lined up for July and I’ll see you on the other side.

Walnut Tree Island sits in a tributary of the Thames and back in the 1960s its part derelict became a sought after music venue, thanks to the work of its owner George. Based on Eel Pie Island, Walnut Tree is a harmonious combination of up and coming musicians, artists and picturesque riverboats and in 1965 is a weekly Mecca for young people. One of them is Mary Star, a young girl with a beautiful voice and a head full of dreams. It’s there one night when musician and up and coming front man Ossie Clark notices Mary in the crowd as she’s hoisted up on someone’s shoulders. Ossie is about to hit the big time, but he’s captivated by Mary and when he meets her he encourages her to sing with him. They are so in love and lay down in the grasses by the Wilderness – the most beautiful part of the island. When reality hits Mary knows she has to make a choice for both of them, although Ossie doesn’t reject the idea of becoming a father. He asks her to go to America with him, but the adults in her life, including George, make her realise how difficult that’s going to be. There will be compromises and although Ossie can’t see it now, what if he resents her and their baby? She’s left with her baby Ruby and a broken heart, but also a place to live on the island gifted by George.

Years later her granddaughter Jo experiences first love on the island. Used to running wild between Mary’s cottage Willows and houseboats, she meets George’s grandson Oliver when he visits the island. He’s the island’s heir, but such things don’t matter to young people and they have a magical summer thinking their love is all they need to sustain them. Now Oliver has returned from NYC as the new owner of Walnut Tree Island which has become a thriving community of musicians and artists all supported by Mary who is the mother of the community. The whispers over what might happen to the island start fairly quickly, not least the ownership of Willows that has always been a verbal agreement with George. Jo now teaches art to children in one of the houseboats. Once an incredible artist she seems to lose her confidence in creating and her career never fully got off the ground. How will she cope with Oliver back on the island, as handsome as ever, but with a touch of New York sophistication? More to the point, how will Oliver feel seeing Jo again? It’s not long before the red-headed firebrand is at his door, fighting on behalf of Mary and the rest of the community. But does she really know what his plans are? Changes are coming to the island, but some things are as constant as the river flows. Could their love be one of them? This is a captivating and magical read, thanks to its romantic setting and relatable female characters. An excellent holiday read.

Emily and Freddie have been through the mill of late. After a terrible accident when they were on holiday, Freddie has surprised her with the home of their dreams. Emily fell from a cliff on a group holiday and not only did she break her leg in several places, she then developed sepsis and almost lost her life. Now she’s in recovery, still walking on a stick and has been thrust into a whole new life. Larkin Lodge sits just outside a village on the edge of the moors and could be their dream home, but Emily can’t believe Freddie made this huge decision without her. The house is gothic and in the mists and murk of winter it looks a little isolated and spooky. However, she can see that in spring the views will be incredible. As Freddie continues to work in London, Emily spends a lot of time alone and starts to feel uneasy. Sudden drafts and disgusting smells, then heavy footsteps moving across the second floor are unnerving. Freddie is convinced she’s struggling with post concussion syndrome and calls her ITU consultant for advice – much to Emily’s disgust for doing this behind her back. As she starts to look into the history of the house and questions some of the locals, all the different parts of her life start to fall apart. Secrets start to come to light and Emily wonders if the house is having an influence on her.

Emily is a sympathetic narrator although she’s not entirely reliable. It must be so disorientating to wake from a coma and know that your body has been present but your mind has been somewhere else. Added to that is the risk of ICU psychosis – a common condition causing auditory hallucinations, nightmares, sleep disturbances and paranoia. The author cleverly creates tension between what we know about Freddie and Emily and what they know about each other. They’re both keeping secrets and Freddie projects all their problems on to her. Even when she’s quite measured and reasonable or accepts his apologies he becomes angrier. Just occasionally he pauses and wonders where these thoughts are coming from? Is it the shock of Emily’s fall still working on him or is something more insidious at work? Of course it wouldn’t be a Sarah Pinborough novel without a supernatural element and this one is genuinely scary. It begins with the window on the landing, seemingly opening of it’s own accord. When she starts talking to older locals about the house there’s a moment that genuinely made the hair stand up on the back of my neck! The chapters from the raven’s perspective are very touching as well as creepy. Was this an edge of the seat thriller or a ghost story? We’re never quite sure, but I felt compelled to keep reading and find out. Sarah Pinborough is the Queen of this type of gothic thriller and this was another brilliant read, keeping you guessing till the very end.

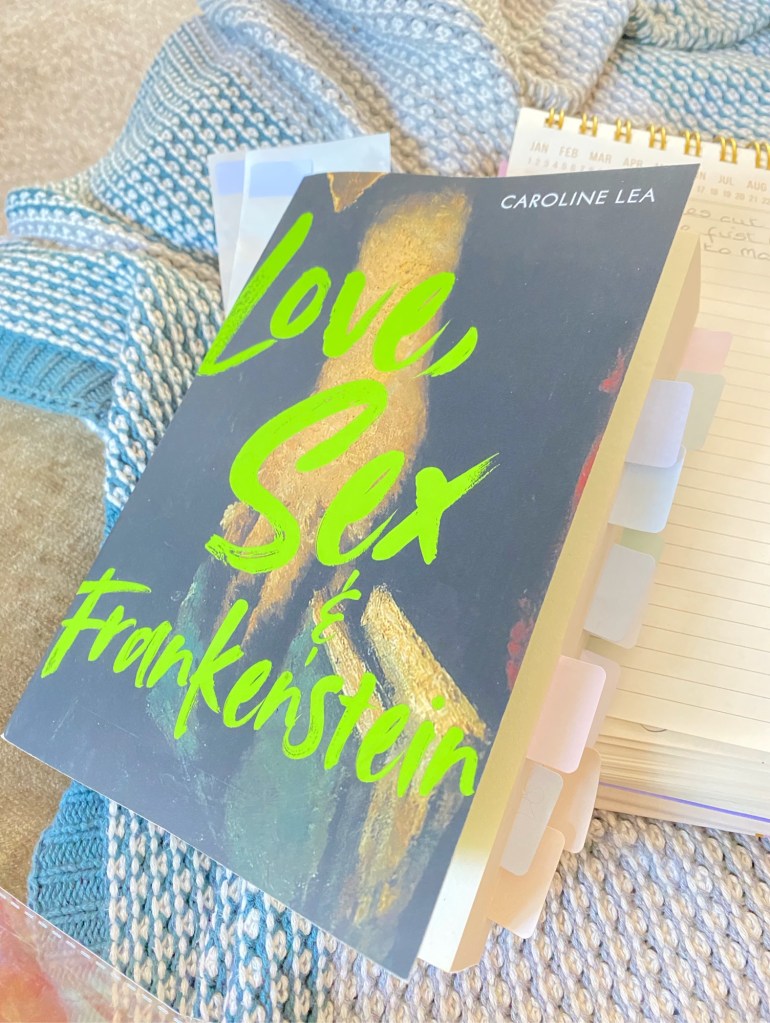

This book is definitely up there for my book of the year so far and it will take something momentous to knock it from that position. It’s the story of Mary Shelley and the origins of her novel Frankenstein which became a staple of the horror genre. I’d always known that it was a novel of monstrous birth, but the author has pulled all the ideas together so we can see the psychological background of the novel. I loved the idea that her story is stitched together by fragments, just like the monster himself. Her own emotions and thoughts feed into the emotions of the abandoned monster. She thinks of medical experiments and stories of medical students digging up bodies and stealing them for dissection. Frankenstein leaves his monster just as Shelley left Mary and their baby in squalor in London at the mercy of bailiffs. Frankenstein can be read as a criticism of men, creating with no thought for the thing they’ve created. Victor Frankenstein goes to sleep expecting his creature to die and feels nothing. The creature feels a combination of Mary’s grief and abandonment, having lost her mother at birth and then the losing of her father, as she runs away with Shelley, a married man. William Godwin brought Mary up to have a rebellious spirit and think for herself, but rejects her when she lives by these principles. Mary is this bewildered and angry creature and she gives her monster the equivalent of philosopher John Locke’s tabula rasa – the blank slate of a small child ready to experience nature, love and all that is beautiful. He embodies the nature/nurture debate in that the creature isn’t born evil, it’s other people’s cruel treatment of him that makes him monstrous. Her writing helps process all these feelings and. working through them makes her feel hopeful for the first time. She might return to London with her son and instead of being beholden to Shelley or her father, she could keep them both with her own writing.

Typically, blinded by his own arrogance Shelley doesn’t see himself in Victor Frankenstein at all. The book, like the creature at its centre, will be sent out into the wilderness looking for a creator. She’s fairly sure it will find one because she knows it’s special. Caroline’s book is an absolute masterpiece and made me think about Frankenstein from so many different angles. Caroline Lea’s Mary take us through the psychological angles and brings to life her relationship with Shelley, often told in a rather salacious or romantic way without any thought to the inequality between them. It traces the genesis of this incredible novel. It is stitched together from so many different parts, but here we can see them all and understand the circumstances they come from. What she’s written is a Bildungsroman, a novel of Mary growing up from girl to womanhood. Frankenstein is the chronicle of that birth, as messy, terrifying, horrific and momentous it is, it is also the genesis of Mary Shelley the writer.

London 1990s – An up and coming French composer called Stan is invited to arrange music for a stage production of Dorian Gray. Although the play is never staged, he does meet Liv and she becomes the love of his life. They live together, joined by a daughter called Lisa. Their happiness fuels his senses with vibrant colours and melodious music. Paris, Present Day – Stan lives in France at the Rabbit Hole, a house left to him by his aunt. He now shares his life with Babette, a lifeguard and mother of a teenage boy of Lisa’s age. They also share their home with Laïvely, a machine built by Stan and given Liv’s voice. As Stan becomes more engrossed in his past Laïvely starts to take on a life of her own. His life is about to implode.

Stan presents his life in two narratives, the present in France and the past where he was at his most creative, happy and in love. His relationship with Liv is almost idyllic. Anything he relates of his present can only suffer in comparison. We learn that he and Babette are compatible, but there is none of the life and vivid colour that comes from his reminiscence. We are all nostalgic about the past, but no relationship can be perfect especially when cramped into the average London apartment with a small baby. While it is touching and romantic, the cynic in me wondered was this a true picture? As for Liv, she is in technicolour in Stan’s flashbacks with her vivid red hair. However, all that life is now reduced to a communication device and no matter how Stan cuddles Laïvely to him, she is inanimate, merely a machine. In what way is this a fitting representation of the love of his life? The author brings the truth to light brilliantly and I feared Stan’s mind was splitting. Stan seems to imagine that he and Liv would have lived in this harmonious way forever, but as the truth emerges Stan’s perception of himself starts to shatter. Babette finds him catatonic and soaking wet, having to place him in a hot bath and slowly bringing him back to himself. It’s the most nurturing, selfless and loving part of the book and it’s all the more sad that he hasn’t before recognised or rewarded her love and loyalty. He also realises that there were times he was too distant and distracted with Liv, that he stopped paying her attention. It was as if he had imagined them always walking towards a common goal but truthfully, he knows they were out of pace with one another. As the ‘tick, tock’ of the clock at the Rabbit Hole reminds us that the end is approaching we fully comprehend this heartbreaking story. This is no ordinary loss and it’s clear that Stan has never faced the truth of their final days until now. This is an emotional end that has one final twist to impart and it is devastating. It seems that Stan has always held on to Liv’s portrait, but is was a ‘painting turned against the wall’, keeping it’s secrets until that final terrible reveal.

It was so lovely to be back in Adriana Trigiani’s world. It always feels like a hug in a book! Jess (short for Guiseppina Capidimonte Baratta) is an artist who designs pieces made with marble, everything from a garden fountain to a baptismal font. She lives with her family in the New Jersey town of Lake Como. Ever since she finished school Jess has worked with her uncle Luis at his marble business, shipping newly quarried Italian marble to the United States. Jess is at a stage in life when she’s longing for something new. After divorcing her childhood sweetheart and local heartthrob Bobby Bilancia she’s been living in her parent’s basement. Their mothers, who have a long held friendship, are openly praying for their reconciliation. Jess could see her whole life mapped out, in fact her namesake Aunt Guiseppina has given her the blueprint – the maiden aunt, chief baby sitter for her sibling’s kids, cook and bottle washer for family dinners, and eventually caring for their elderly parents. When the family experience an unexpected loss, coupled with financial worries, secrets come tumbling out of every closet. Jess decides to take the trip to Italy that had been planned for work. Now she’ll use it as a change of scene rather than just a work trip. Finally, she will see her ancestor’s homeland. Taking us to Lake Como via Milan, Jess falls in love with Italy and all it has to offer.

This story is a common narrative in the author’s novels. A young, ambitious and talented woman is looking for a lucky break or a foothold in the family business and has an adventure. Jess is slightly different in that she’s older and has already found her Prince Charming once. Stressful situations usually floor Jess, who has suffered from anxiety all her life. The family carry brown paper bags wherever they go. Yet Jess has withstood the questions and judgement about her divorce and sticks with her decision, only confiding in her online counsellor and her journal. She sets out to her Uncle Louis’s hometown to visit the marble quarries that supply their marble but also meet with local stonemasons who use it. It should be useful for her work but also give her the head space she needs after the divorce, her loss and those family home truths that left her very angry with her parents. When she meets Angelo Strazzi, a talented local craftsman, there’s instant chemistry and future possibilities start to open up. As always Italy is a revelation and Trigiani writes about it in a way that only an Italian American can. There’s familiarity and nostalgia that comes from knowing her family are from here, but there’s also the wonder and magic of the tourist view too. It’s the best of both worlds. Mostly I loved that Italy seems to set Jess free, in her own right. She’s away from a community that claims to know her better than she knows herself, but also from the suffocating combination of her own family and that of her ex-husband. Free from a future that she and her family saw for her – that of the maiden aunt. Maybe it’s the mountains but Jess can breathe in Italy. I came out of the novel feeling like I’d been on holiday. I won’t ruin the book by telling you what Jess’s choices are, but the ending isn’t the only important thing. I hope you enjoy the journey as much as I did.

I was three quarters of the way through this novel before I found out it was based on a true story. Zara was a fashion designer, founding a dress shop called Magg with her best friend Betty in her twenties. Freeman’s novel follows Zara’s life from her meeting with Harry Holt and their relationship, which would dominate most of her life. The novel takes us on her travels, into her career as a fashion designer and businesswoman and the volatility of her relationship with Holt. Harry comes across as a selfish and ambitious man, who clearly loved Zara but was slow to commit and couldn’t curb his womanising ways. Zara is constantly waiting, whether it’s for him to propose marriage or to be faithful to her. She is torn between wanting a monogamous relationship or accepting both Harry’s love and the fact it comes with many compromises on her part. I’m not sure I could have made those compromises, but despite breaking off their relationship and even marrying an officer from the British Army and living in India, she finds it impossible to leave behind those feelings. Aside from her love life, Zara is a remarkable woman and one of those multi-tasking geniuses I envy. She managed to create an empire that paid for the couple’s holiday homes on different parts of the Australian coast and even when on political trips abroad, particularly as Harry was moving towards becoming prime minister, she used local fashions as inspiration and bought fabric to be shipped back. I had to remind myself I was reading a historical novel when frustrated with societal expectations and attitudes, because Zara was such a modern woman and seemed ahead of her time.

As always I have a loose tbr for July while I’m project managing our kitchen renovation. I’ll be frazzled by the time it’s done as I hate change and noise, but I’ll need to be at home so lots of reading time ❤️📚