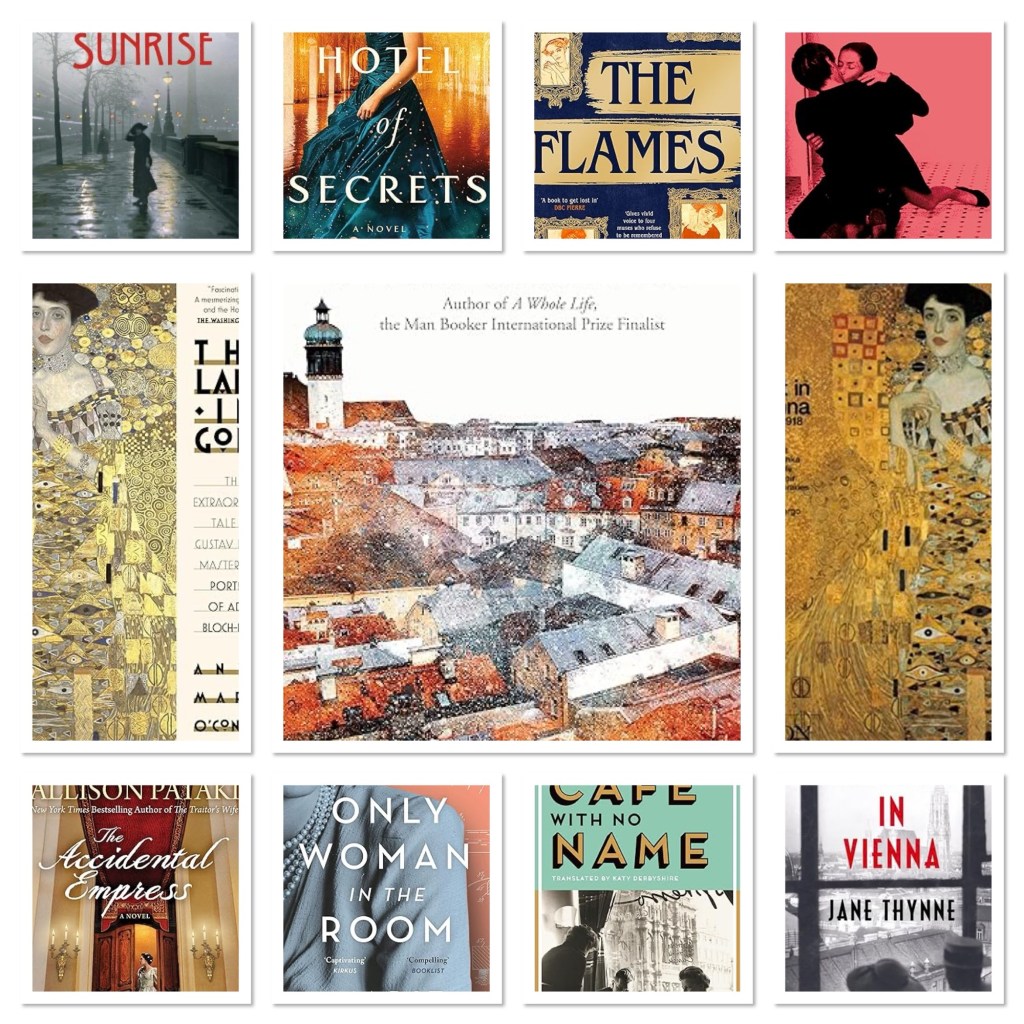

I’ve never been to Vienna but it’s very firmly on my list of places I’d like to visit. Firstly I love Klimt with a passion and have been to any and every exhibition of his work, but never in his homeland. I’m also interested in Freud, for obvious reasons. I’d like to eat a piece of Sachertorte there too. For now I’ll have to keep reading books set in the city.

Set in 1938 in London and Vienna, this is a tense and atmospheric thriller told from within a climate of uncertainty and fear as World War Two threatens. As war looms over Britain and there is talk of gas masks and blackout, people are understandably jumpy and anxious. Stella Fry, has been working in Vienna for a Jewish family and returns home with no job and a broken heart. She answers an advertisement from a famous mystery writer, Hubert Newman, who needs a manuscript typed. She takes on the job and is shocked the next day to learn of the writer’s sudden, unexplained death. She is even more surprised when, twenty-four hours later, she receives Newman’s manuscript and reads the Dedication: To Stella, spotter of mistakes. Harry Fox, formerly of Special Branch and brilliant at surveillance, has been suspended for some undisclosed misdemeanor. He has his own reasons for being interested in Hubert Newman. He approaches Stella Fry to share his belief that the writer’s death was no accident. What’s more, since she was the last person to see Newman, she could be in danger herself.

It is 1966, and Robert Simon has just fulfilled his dream by taking over a café on the corner of a bustling Vienna market. He recruits a barmaid, Mila, and soon the customers flock in. Factory workers, market traders, elderly ladies, a wrestler, a painter, an unemployed seamstress in search of a job, each bring their stories and their plans for the future. As Robert listens and Mila refills their glasses, romances bloom, friendships are made and fortunes change. And change is coming to the city around them, to the little café, and to Robert’s dream.

A story of the hopes, kindnesses and everyday heroism of one community, The Café with No Name has charmed millions of European readers. It is an unforgettable novel about how we carry each other through good and bad times, and how even the most ordinary life is, in its own way, quite extraordinary.

Hedy Lamarr possessed a stunning beauty. She also possessed a stunning mind. Could the world handle both?

Her beauty almost certainly saved her from the rising Nazi party and led to marriage with an Austrian arms dealer. Underestimated in everything else, she overheard the Third Reich’s plans while at her husband’s side, understanding more than anyone would guess. She devised a plan to flee in disguise from their castle, and the whirlwind escape landed her in Hollywood. She became Hedy Lamarr, screen star.

But she kept a secret more shocking than her heritage or her marriage: she was a scientist. And she knew a few secrets about the enemy. She had an idea that might help the country fight the Nazis…if anyone would listen to her.

A powerful novel based on the incredible true story of the glamour icon and scientist whose groundbreaking invention revolutionised modern communication, The Only Woman in the Room is a masterpiece.

The year is 1853, and the Habsburgs are Europe’s most powerful ruling family. With his empire stretching from Austria to Russia, from Germany to Italy, Emperor Franz Joseph is young, rich, and ready to marry.

Fifteen-year-old Elisabeth, “Sisi,” Duchess of Bavaria, travels to the Habsburg Court with her older sister, who is betrothed to the young emperor. But shortly after her arrival at court, Sisi finds herself in an unexpected dilemma: she has inadvertently fallen for and won the heart of her sister’s groom. Franz Joseph reneges on his earlier proposal and declares his intention to marry Sisi instead.

Thrust onto the throne of Europe’s most treacherous imperial court, Sisi upsets political and familial loyalties in her quest to win, and keep, the love of her emperor, her people, and of the world.

With Pataki’s rich period detail and cast of complex, bewitching characters, The Accidental Empress offers a glimpse into one of history’s most intriguing royal families, shedding new light on the glittering Hapsburg Empire and its most mesmerizing, most beloved “Fairy Queen.”

Erika Kohut teaches piano at the Vienna Conservatory by day. By night she trawls the city’s porn shows while her mother, whom she loves and hates in equal measure, waits up for her. Into this emotional pressure-cooker bounds music student and ladies’ man Walter Klemmer.

With Walter as her student, Erika spirals out of control, consumed by the ecstasy of self-destruction. A haunting tale of morbid voyeurism and masochism, The Piano Teacher, first published in 1983, is Elfreide Jelinek’s Masterpiece.

Jelinek was awarded the Nobel Prize For Literature in 2004 for her ‘musical flow of voices and counter-voices in novels and plays that, with extraordinary linguistic zeal, reveal the absurdity of society’s clichés and their subjugating power.

The Piano Teacher was adapted into an internationally successful film by Michael Haneke, which won three major prizes at Cannes, including the Grand Prize and Best Actress for Isabelle Huppert.

Vienna at the dawn of the 20th century. An opulent, extravagant city teeming with art, music and radical ideas. A place where the social elite attend glamorous balls in the city’s palaces whilst young intellectuals decry the empire across the tables of crowded cafes. It is a city where anything seems possible – if you are a man.

Edith and Adele are sisters, the daughters of a wealthy bourgeois industrialist. They are expected to follow the rules, to marry well, and produce children. Gertrude is in thrall to her flamboyant older brother. Marked by a traumatic childhood, she envies the freedom he so readily commands. Vally was born into poverty but is making her way in the world as a model for the eminent artist Gustav Klimt.

None of these women is quite what they seem. Fierce, passionate and determined, they want to defy convention and forge their own path. But their lives are set on a collision course when they become entangled with the controversial young artist Egon Schiele whose work – and private life – are sending shockwaves through Vienna’s elite. All it will take is a single act of betrayal to change everything for them all. Because just as a flame has the power to mesmerize, it can also destroy everything in its path…

It’s Ball Season in Vienna, and Maria Wallner only wants one thing: to restore her family’s hotel, the Hotel Wallner, to its former glory. She’s not going to let anything get in her way – not her parents’ three-decade-long affair; not seemingly-random attacks by masked assassins; and especially not the broad-shouldered American foreign agent who’s saved her life two times already. No matter how luscious his mouth is. Eli Whittaker also only wants one thing: to find out who is selling American secret codes across Europe, arrest them, and go home to his sensible life in Washington, DC. He has one lead – a letter the culprit sent from a Viennese hotel. But when he arrives in Vienna, he is immediately swept up into a chaotic whirlwind of balls, spies, waltzes, and beautiful hotelkeepers who seem to constantly find themselves in danger. He disapproves of all of it! But his disapproval is tested as he slowly falls deeper into the chaos – and as his attraction to said hotelkeeper grows. Diana Biller’s The Hotel of Secrets is chock full of banter-filled shenanigans, must-have-you kisses, and romance certain to light a fire in the hearts of readers everywhere.

Vienna, 1913. It is a fine day in August when Lysander Rief, a young English actor, walks through the city to his first appointment with the eminent psychiatrist Dr Bensimon. Sitting in the waiting room he is anxiously pondering the particularly intimate nature of his neurosis when a young woman enters. She is clearly in distress, but Lysander is immediately drawn to her strange, hazel eyes and her unusual, intense beauty. Her name is Hettie Bull. They begin a passionate love affair and life in Vienna becomes tinged with a powerful frisson of excitement for Lysander. He meets Sigmund Freud in a café, begins to write a journal, enjoys secret trysts with Hettie and appears – miraculously – to have been cured. Back in London, 1914. War is imminent, and events in Vienna have caught up with Lysander in the most damaging way. Unable to live an ordinary life, he is plunged into the dangerous theatre of wartime intelligence – a world of sex, scandal and spies, where lines of truth and deception blur with every waking day. Lysander must now discover the key to a secret code which is threatening Britain’s safety, and use all his skills to keep the murky world of suspicion and betrayal from invading every corner of his life. Moving from Vienna to London’s West End, from the battlefields of France to hotel rooms in Geneva, Waiting for Sunrise is a feverish and mesmerising journey into the human psyche, a beautifully observed portrait of wartime Europe, a plot-twisting thriller and a literary tour de force from the bestselling author of Any Human Heart, Restless and Ordinary Thunderstorms.

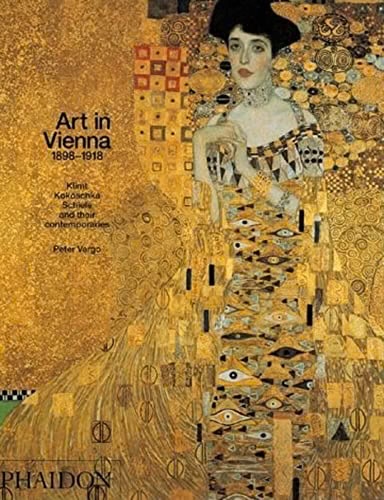

The artistic stagnation of Vienna at the end of the nineteenth century was rudely shaken by the artists of the Secession. Their works at first shocked a conservative public, but their successive exhibitions, their magazine Ver Sacrum and their dedication to the applied arts and architecture soon brought them an enthusiastic following and wealthy patronage. With 60 new colour illustrations, this classic book, now in its third edition, brilliantly traces the course of this development, of the Wiener Werkstätte that followed, and the individual works of the artists concerned. The result is a fascinating documentary study of the successes and failures, hopes and fears of the members of an artistic movement that is so much admired today.

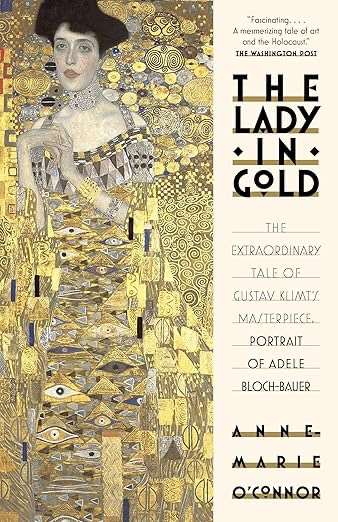

This is the true story that inspired the movie “Woman in Gold” starring Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds. Anne-Marie O Connor brilliantly regales us with the galvanizing story of Gustav Klimt’s 1907 masterpiece, the breathtaking portrait of a Viennese Jewish socialite, Adele Bloch-Bauer. The celebrated painting, stolen by Nazis during World War II, subsequently became the subject of a decade-long dispute between her heirs and the Austrian government.When the U.S. Supreme Court became involved in the case, its decision had profound ramifications in the art world. Expertly researched, masterfully told, “The Lady in Gold” is at once a stunning depiction of fin-de siecle Vienna, a riveting tale of Nazi war crimes, and a fascinating glimpse into the high-stakes workings of the contemporary art world.

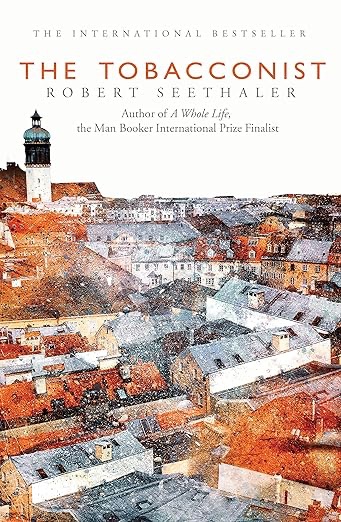

Seventeen-year-old Franz Huchel journeys to Vienna to apprentice at a tobacco shop. There he meets Sigmund Freud, a regular customer, and over time the two very different men form a singular friendship. When Franz falls desperately in love with the music hall dancer Anezka, he seeks advice from the renowned psychoanalyst, who admits that the female sex is as big a mystery to him as it is to Franz.

As political and social conditions in Austria dramatically worsen with the Nazis’ arrival in Vienna, Franz, Freud, and Anezka are swept into the maelstrom of events. Each has a big decision to make: to stay or to flee?