The Classics

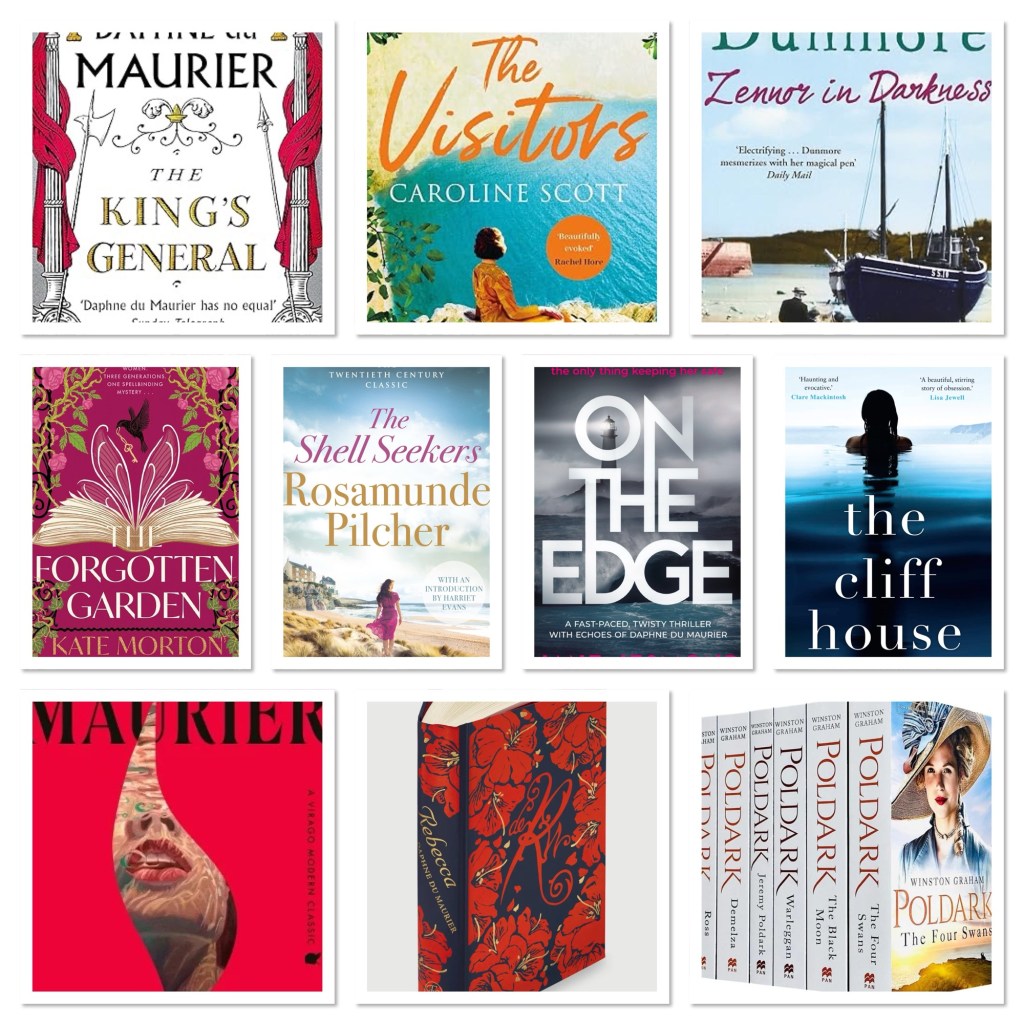

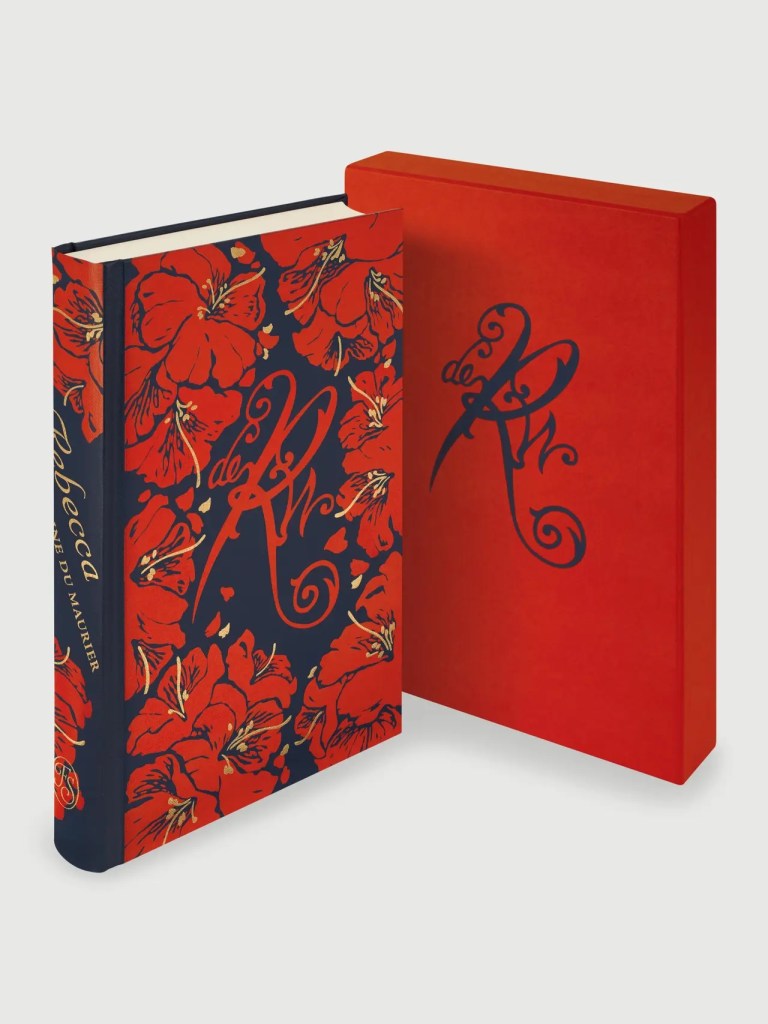

Rebecca is probably the reason I first visited Cornwall, but it’s also one of those books that I’ve changed my mind about when I reread it. I read the book as a teenager from mum’s bookshelf and I also watched the Hitchcock film at a similar age and both book and film are still favourites. I think I read it as a romance at first, rooting for the rather young and mousy heroine as she falls in love with brooding stranger Maxim de Winter as they meet in Monte Carlo. Now I read it as an altogether different story, probably emphasised by the above new Virago edition that’s billed as one of her ‘dark romance’ books. Maxim is dazzlingly and tragically romantic to our young heroine, mourning the wife who was known as a great beauty and unable to be in their Cornish stately home Manderlay. Perched on the cliffs near Fowey and based on de Maurier’s home Menabilly, this is one of the most beautiful and gothic settings. It’s impossible to see from the road, only from the sea and its private beach only accessible by boat or on treacherous steps from the grounds of the house. The heroine does seem to win it all – the man, the house, the money and love – but does she really? Immediately invisible next to the dark and sexy Rebecca of the title, the new Mrs de Winter doesn’t even warrant her own name. She’s scared of running the house having never done it, she’s not even the same class. She’s also scared of the servants, especially the creepy maid of his first wife, Mrs Danvers. At one point she breaks a statue in the morning room and hides the evidence. Maxim is no help. Instead of appointing a servant to help with decisions in the house, or at least to bring her up to speed, he just goes out first thing and leaves her to the brooding and obsessive Mrs Danvers, now the housekeeper. Max has no idea how privileged he is and can’t comprehend her hesitancy and fear of getting it wrong and when she does he flies into a temper or scolds her like a child. He gaslights, lies and yells at her. She may as well have been poured into a pit of vipers. This has never been a love story, it’s more a gothic retelling of Jane Eyre and origin of the domestic noir genre. This is an absolute Cornish classic from one of their most famous writers.

https://www.foliosociety.com/uk/rebecca

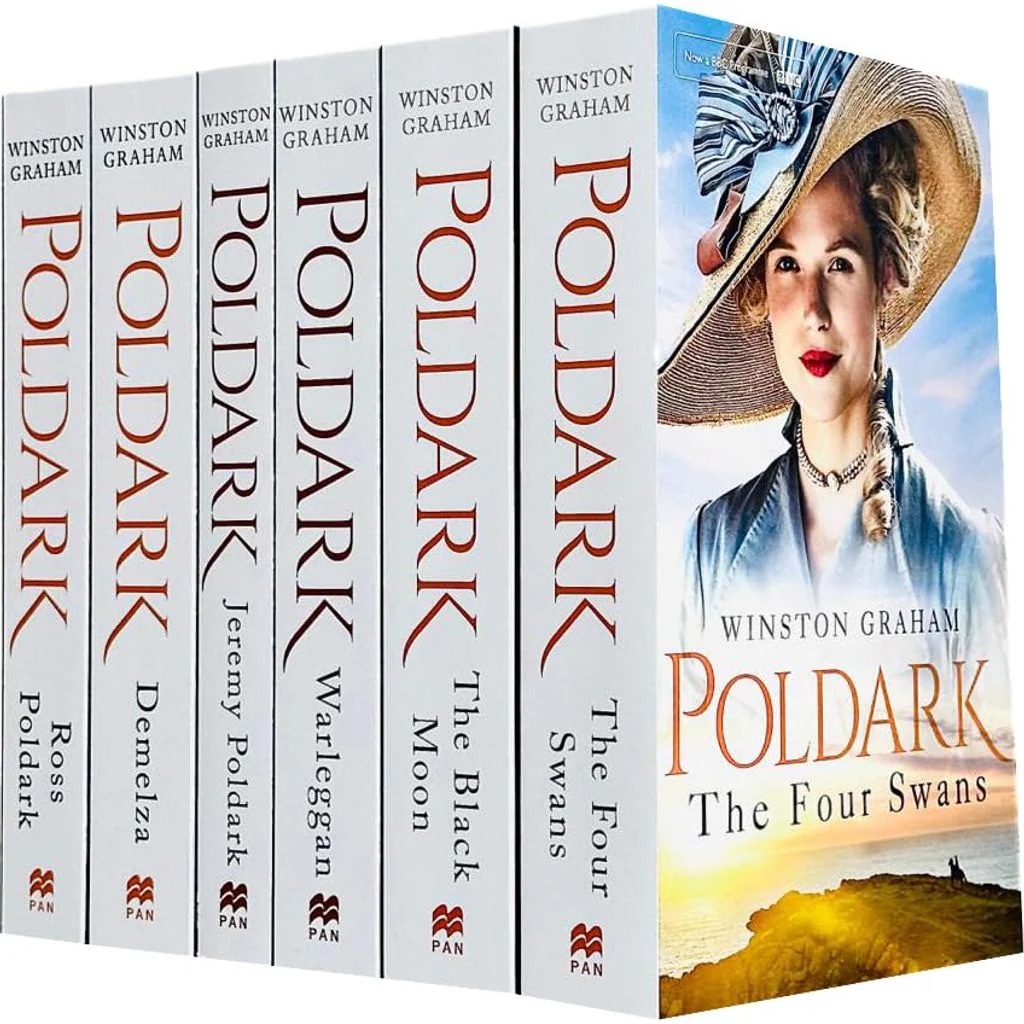

The Poldark Novels by Winston Graham

The Poldark novels had a resurgence and series of new editions thanks to the new BBC series which dominated Sunday nights and starred Aiden Turner as Ross Poldark and Eleanor Tomlinson as his wife Demelza. They begin in the late eighteenth century as Poldark returns from the American Revolutionary War to his home county of Cornwall and the Poldark house and land. Things have changed since he left. His father is dead and the copper mine is failing. His sweetheart Elizabeth has become engaged to Ross’s cousin George and they will be living at Trenwith with Ross’s grandmother. There are differences between the books and the TV series. Demelza is actually a child when Ross first meets her and he takes her to be one of the staff at the smaller farm estate of Nampara. There are ten years in age between them and it’s only when she’s an older teenager that their relationship changes – in the series he brings her as an adult and marries her very quickly, much to the disgust of his parish. I think the books are grittier than the tv series, with the main characters having more complexity and actually doing things we might not like. Ross particularly has more ambiguity, a good man when it comes to his workers and his politics but not such a great husband. The abuse and rape suffered by Morwenna in the marriage forced by Warleggan hits harder. The series really deviates after book three with no exploration of the children as they grow up and the terrible grief they go through as parents. I think the series wanted to paint Ross and Demelza as a love story with a happy ending after a tough period following infidelity, but in the books life goes and Ross’s rivalry with George Warleggan still continues, even when they’re older men. I think the books give more of that historical background, particularly with the backdrop of war and later the Industrial Revolution. It’s almost as if the series is the tourist’s view and the books place the characters more firmly in their time period.

Mysteries and Thrillers

When I read a more recent Ruth Ware thriller I went back to some of her earlier books and I inhaled this in two sittings. We follow Harriet Westaway as she receives an unexpected letter telling her she’s inherited a substantial bequest from her Cornish grandmother. Could this be the answer to her prayers?

There’s just one problem – Hal’s real grandparents died more than twenty years ago. Hal considers her options, she desperately needs the cash and makes a choice that will change her life for ever. She knows that her skills as a seaside fortune teller could help her con her way to getting the money and once Hal embarks on her deception, there is no going back. This keeps you on tenterhooks from the minute Hal arrives at Trespassen House in Cornwall and there is that hint of Daphne du Maurier in the family estate and the mystery that plays out. Hal is also placing herself in a wholly different family and social class. Her upbringing may have been short on money, but it was never short on love. The tragic death of her mother Maggie was only three years ago and it catapulted Hal into adulthood but the Westaway family don’t hold the same values. They do have secrets though, ready to drop out of every closet. She is the outsider here, totally out of her depth and the wild coastline, storm porch and St Piran’s Church place this firmly in Cornwall. This family may have money and privilege but they don’t have the love or care for each other that Hal is used to, she will have to use her skills of perception and discernment honed by years of tarot reading. The remoteness of Trespassen and lack of internet signal add to the Gothic feel of this novel and there is even a Mrs Danvers mentioned. This is a great thriller with plenty of clues but a lot of red herrings, so you must be prepared for surprises.

Tamsyn is as local as it getsin their Cornish village. Her grandfather worked the tin mines, her father was a lifeboat volunteer alongside his work, but her brother is struggling to find work that’s not seasonal. Tamsyn’s attachment to The Cliff House to a beautiful coastal property just outside her village comes to a head in the summer of 1986. To her, the house represents an escape, a lifestyle that’s completely out of range for her and represents the perfect life. It’s also her last link to her father, who brought her here to swim in the pool when he knew the owners were away. Her father felt rules were made to be broken and they both considered it madness to own such a slice of perfection overlooking the sea yet rarely visit except for a few weeks in the summer. Now he’s gone, Tamsyn watches the Cliff House alone and views it’s owners, the Davenports, as the height of sophistication. Their life is a world away from her cramped cottage, her Granfer’s coughing into red spattered handkerchiefs and their constant struggle for money.

Tamsyn’s family are firmly have nots. Her hero father died rescuing a drowning child and now she has to watch her mother’s burgeoning friendship with the man who owns the chip shop. Her brother is unable to find steady work, but finds odd jobs and shifts where he can, to put his contribution under the kettle in the kitchen. Mum works at the chip shop, but is also the Davenport’s cleaner. She keeps their key in the kitchen drawer, but every so often Tamsyn steals it and let’s herself in to admire Eleanor Davenport’s clothing and face creams and Max’s study with a view of the sea. Yet, the family’s real lives are only a figment of her imagination until she meets Edie. When Tamsyn finally becomes involved with the Davenports she gets to see the reality of a family bathed in privilege. As we try and work out Tamsyn’s motivations, she seems blind to the problems and ticking time bomb at the centre of the family. Or is she more perceptive than we think? This is a great thriller with disturbing family dynamics and an interesting tension between second homers and those who live in Cornwall all year round and struggle to own a home. The rugged cliffs and raging sea are a beautiful, dangerous and fitting backdrop to this tension.

Another book highlighting the dangerous beauty of the Cornish coast is Jane Jesmond’s first thriller On The Edge. I was thoroughly gripped by this tense thriller set in Cornwall concerning Jenifry Shaw – an experienced free climber who is in rehabilitation at the start of the novel. She hasn’t finished her voluntary fortnight stay but is itching for an excuse to get away when her brother Kit calls and asks her to go home. Sure that she has the addiction under control, she drives her Aston down to her home village and since she isn’t expected, chooses to stay at the hotel rather than go straight to the family home. Feeling restless, she decides to try one of her distraction activities and goes for a bracing walk along the cliffs. Much later she wakes to darkness. She’s being lashed by wind and rain, seemingly hanging from somewhere on the cliff by a very fragile rope. Every gust of wind buffets her against the surface causing cuts and grazes. She gets her bearings and realises she’s hanging from the viewing platform of the lighthouse. Normally she could climb herself out of this, most natural surfaces have small imperfections and places to grab onto, but this man made structure is completely smooth. Her only chance is to use the rapidly fraying rope to climb back to the platform and pull herself over. She’s only got one go at this though, one jerk and her weight will probably snap the rope – the only thing keeping her from a certain death dashed on the rocks below. She has no choice. She has to try.

My heart was racing during the opening of this novel and I was so hooked I read it in one sitting. The sense of place was incredible. The author conjured up Cornwall immediately with her descriptions of the tin mine, the crashing sea on the cliffs and fog on the moors. I recognised the sea mist that seems to coat your car and your windows. The weather was hugely important, with storms amping up the tension in the opening chapters and the fog of the final chapters adding to the mystery. Will we find out who is behind the strange and dangerous events Jen has uncovered or will it remain obscured? Cornwall is the perfect place to hide criminal activity, hence the history of smuggling and piracy, so why would it be any different today? Has the cargo changed? I loved that the author wove modern events and concerns into the story, because it helped the story feel current and real. The concerns around development and tourism are all too real for a county, dependent on the money tourism brings, but trying to find a balance where it doesn’t erode the Cornish culture. Local young people are priced out of the property market completely. This is a great combination of setting and edge of your seat thriller, with a character as wild as the coastline.

Family Sagas

This book makes me nostalgic for the times I’ve spent in Cornwall. It also makes me want to go on RightMove and look for a little shop I can turn into a bookshop and writing therapy centre. Enough of my daydreams. I think this is one of those books that modern readers avoid because the covers have been too feminine and floral, marking it out as a romance when really it’s a family drama ( i want to use the word sweeping when I think about). Penelope is elderly and while she is recovering from a heart attack she thinks about the years she spent in Cornwall. What follows is the story of a family—mothers and daughters, husbands and lovers—and the many loves and heartbreaks that have held them together for three generations. It’s a magical novel, giving the kind of reading experience you can get swept away in for hours. Penelope prized possession is The Shell Seekers, painted by her father. It seems to symbolise her unconventional life, from her bohemian childhood to WWII romance. When her grown children learn their grandfather’s work is now worth a fortune, each has an idea as to what Penelope should do. But as she recalls the passions, tragedies, and secrets of her life, she knows there is only one answer…and it lies in her heart.

One of my favourite places in the world is Watergate Bay and I feel energised just by standing on that beach and feeling the sea spray hit my face. This book gave me the same feeling because you can feel Pilcher’s love for Cornwall throughout. It also made me grateful for a family who don’t care about money, just about love. This is a fabulous holiday read so don’t be put off by the cover.

In Kate Morton’s second novel she takes us through a family’s history with Gothic undertones, contrasting the beautiful setting of Cornwall with 19th Century London. It covers three timelines over three generations of women, all caught up in one compelling mystery.

Once, a little girl was found abandoned after a gruelling sea voyage from England to Australia. She carried nothing with her but a small suitcase of clothes, an exquisite volume of fairy tales and the memory of a mysterious woman called the Authoress, who promised to look after her but then vanished. Years later, Nell returns to England to uncover the truth about her identity. Her quest leads her to the strange and beautiful Blackhurst Manor on the Cornish coast, but its long-forgotten gardens hide secrets of their own. Now, upon Nell’s death, her granddaughter, Cassandra, comes into a surprise inheritance: an old book of dark fairy tales and a ramshackle cottage in Cornwall. It is here that she must finally solve the puzzle that has haunted her family for a century, embarking on a journey that blends past and present, myth and mystery, fact and fable. I am lucky enough to have a new edition of this book to read with my Squad POD next month so look out for my review.

Historical Fiction

My mum was a huge fan of D.H.Lawrence’s books so this book jumped out at me in a second hand bookshop. It’s Helen Dunmore’s first novel published in 1993. Set in the coastal village of Zennor, this covers the time that D.H.Lawrence and his German wife, Freida, laid low during the First World War. In the spring of 1917, at a time when ships were being sunk be U-boats, coastal villages were full of superstition. The Lawrence’s were hoping to escape the war fever in London and chose Cornwall. There, they befriend Clare Coyne, a young artist struggling to console her beloved cousin, John William, who is on leave from the trenches and suffering from shell-shock.

Yet the dark tide of gossip and innuendo is also present in Cornwall, meaning Zennor neither a place of recovery nor of escape. Freida and Lawrence are minor characters, with the main story focused on Clare and suspicions about her relationship with her cousin. Helen is adept at bringing people from history back to life, filling them with emotions and preoccupations that are familiar to us. The Cornish coast is vividly described with its fishing industry, craggy inlets and secret beaches providing a wonderful backdrop to the atmosphere of suspicion especially with the their smuggling history. She captures the claustrophobic feel of a small village where everyone knows each other and incomers are kept at a distance. She also captures how lonely it can be to move into such a close knit community and how lives can be ruined by assumptions.

Caroline Scott’s book is set in the aftermath of WWI in the summer of 1923. Esme Nicholls is drawn into spending the summer in Cornwall, close to Penzance which was the birthplace of her husband. Alec died fighting in the war and she’s hoping to spend some time learning more about the man she fell in love with and lost too soon. She’s been invited to stay in the home of her friend Gilbert, as a potential retreat for the lady she works for, Mrs Pickering. He inherited the rambling seaside house and has turned it into a recovery centre of sorts. All residents are former soldiers, expressing themselves through art or writing. She is nervous to be the only woman, but soon gets to know the men and their stories. They give her insight into what Alec may have experienced and that’s exactly what she needs.

However, this summer retreat is about to change as a new arrival brings with him the ability to turn Esme’s world upside down. She will soon be questioning everything about her life and the people in it. Cornwall is an idyllic backdrop to the story and a huge factor in the recovery and the creative work of these men. Esme’s growing friendships are beautifully drawn and as always I was emotionally invested in her characters. I loved how her relationship with Mrs Pickering softened from being a professional companion to friendship. I also enjoyed her growing closeness to Rory and Hal. They all help with her grief and the shock of this new guest. But as always, holidays come to an end, leaving Esme with huge choices to make.

My Favourite

I first read this wonderful novel when I was a teenager, captured by the romance at the centre of the novel. Then the backdrop really started to sing out to me, especially when I started to regularly visit Cornwall around twenty years ago. Lastly it was the history aspects to the latter parts of the story with our characters caught up in English Civil War and Cornwall’s unique role, both geographically and as staunch Royalists. It’s fair to say that the book wasn’t well received at first, especially after the instant success of Rebecca and My Cousin Rachel. This takes a similar romantic narrative but weaves in the history of a Cornish house that would eventually become her home, Menabilly on the Gribben peninsula near Fowey. At the time of starting her new book it had been owned by the Rashleigh family for over 400 years. Daphne would visit and talk to them about using the house and they told her a story about building work they were having done when builders found a bricked up room housing the skeleton of a Cavalier. She decided to write this real life mystery into the novel wanted to write, when she finally and inevitably overcame their objections.

Her decision to record historical facts truthfully could have been the book’s undoing. The history of the Royalist cause in Cornwall is convoluted and confusing and there’s a large background cast of related Cornish families. I think she wanted to remain faithful to the Cornish cause and be seen to include real Cornish people, but the reader could be forgiven for struggling with them, many names are similar and the intricacies of intermarriage sometimes make the plot hard to follow. Cornwall did declare for the King and our hero Richard Grenvile is the grandson of Sir Richard Grenville who fought the Spaniards in the Azores. He is depicted as flamboyant, with an incredibly fiery temper, but he can be very charming and as time and experience show, he is incredibly loyal. Our heroine Honor Harris is the character I fell in love with possibly because of the fact she’s always reading and is a bit wild. She is absolutely swept off her feet by the man she meets in the family orchard, while sitting in her reading place up in an apple tree. Luckily her hiding place is just big enough for two. Richard is older, a seasoned soldier with wars on the Continent and Ireland under his belt. He is known as ruthless with a terrible reputation. However, he and Honor fall in love. Only a day before their wedding, Honor goes hunting with Richard and his sister. He calls back to warn her about a ravine but his call is lost on the wind and she falls down the precipice. She is then paralysed from the waist down. I think this is possibly why I fell in love with the book, having had my own accident when I was eleven. I had two fractures and a crushed disc, but luckily my spinal cord wasn’t affected. I didn’t finish primary school but returned to start secondary school in the autumn. It has given me problems ever since. It was wonderful to read a character who had a disability but whose fiancé still loved and wanted to marry her, at a time when I was starting to look at boys a little differently.

Despite Richard’s promises, Honor knows she can’t fulfil the role of an army officer’s wife. She decides to let Richard go and gives him her blessing to find someone else. She still follows Richard’s exploits as he moves through Cornwall trying to turn the Royalist sympathisers into an effective fighting force. The Cornish aristocracy have the hereditary right to become fellow commanders, although he finds them incompetent and at times cowardly. Honor has a wheelchair made by her brother, which allows her some movement and at times she manages to support and actually assist Richard. Their love for each other never seems to fade and I enjoyed the romantic aspects of the novel. Their relationship is the spark that lights up this novel, even more so now that I am a wheelchair user at times. I was impressed by how intrepid and determined Honor is and that Daphne wrote a disabled heroine in the 1940s. A couple of years ago, on my honeymoon, I went to Fowey and the Daphne du Maurier bookshop and bought a first edition of the novel for my collection. My old copy was falling apart from re-reading, but I also wanted to own such an important copy of my favourite Cornish novel.