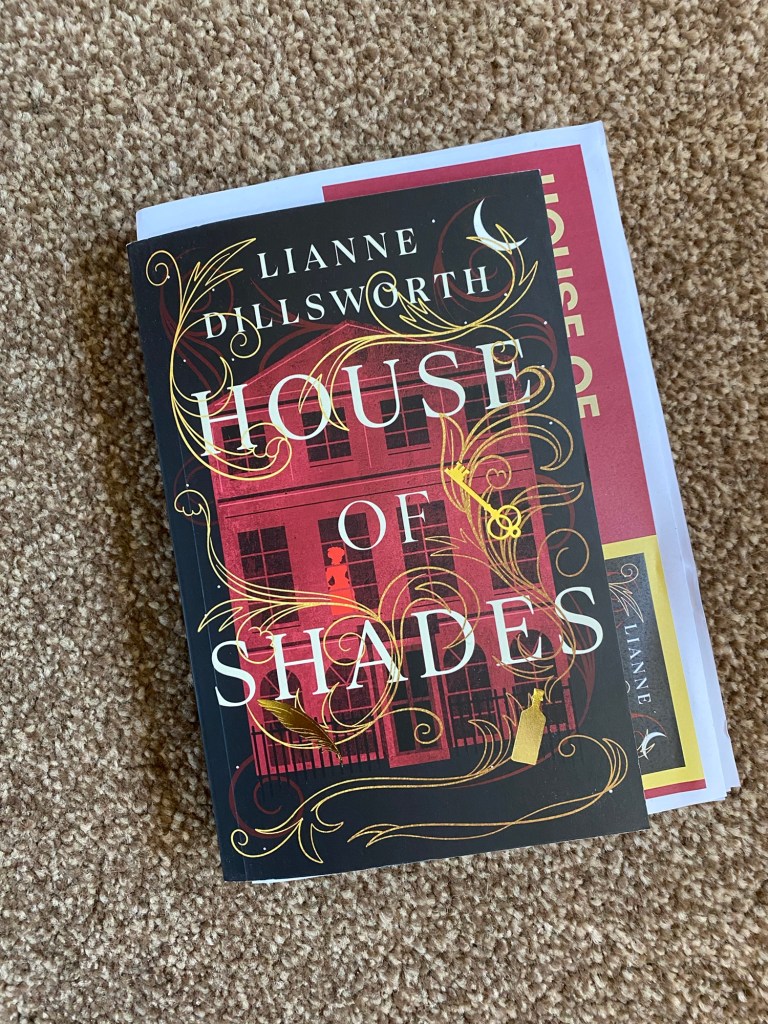

Hester is a doctoress, using her mother’s skills and recipes to treat the ladies of the night around her Kings Cross home. She’s offered a commission to work in the Fitzrovia home of Gervaise Cherville, a rich factory owner with declining health.

If Hester can diagnose and treat his illness he will pay her ten pounds, a life changing amount of money in 1833. Thinking that the fee will help them move to a better area of London, she leaves behind husband Jos and slightly wild sister, Willa, to work at Tall Trees the Cherville mansion. However there’s a dark energy in this old house, as if there’s a curse on Cherville and his mansion.He asks if Hester will track down two women who worked in the house – Aphrodite and Artemis. However, they weren’t servants but slaves and Cherville’s treatment of them torments him and keeps him awake at night. If Hester can find the women, allowing him to make reparation before he dies, he will raise her fee to twenty pounds. Hester is torn, twenty pounds would allow them to move to the country, removing Willa from the temptations that keep her out at night. Yet, will these women want to found, especially given Cherville’s abuses of power? Also, can Hester as a black woman, put another black women in danger without the consequences being on her conscience forever?

Inheritance is a huge theme in the novel and especially, the way in which characters receive their portion. Of course an inheritance isn’t always financial and the intentions of the giver play a large part in what it can do. Hester’s mother has given her an incredible inheritance, her doctoress’s bag of herbs and potions that can ease sicknesses of the mind and body. This of course helps her earn a living, tending to the prostitutes around their part of town at night. Kings Cross is known as a red light district and Hester tends to their venereal diseases, but also their bruises when men take what they want without paying. However, she also has the keeping of her younger sister Willa which isn’t easy. Willa is wild, easily led and naive when it comes to the intentions of men. Hester’s husband Jos finds it difficult living with Willa, especially when the sisters are at odds with each other. Willa works at the Cherville’s factory and has been noticed by Gervaise Cherville’s son, Rowland. It’s clear to Hester that his intentions aren’t honourable, but can she convince her headstrong sister that he isn’t as in love with her as he claims? When working at the Cherville’s house can she stop Rowland from recognising who she is, while also taking care that he doesn’t put undue influence on his father. Rowland isn’t happy with Gervaise giving away ‘his money’ in reparations, after all their plantation has hundreds of slaves and where will his charity end?

I loved the double meaning of the title House of Shades; the shades or ghosts of the past play their part here, especially in the mahogany furniture Cherville had made from the trees on the plantation. However, it also refers to shades of skin colour. I loved how the author explored the concept of ‘passing’ and colourism, especially in the light skinned character Lady Raine. Hester herself is very dark skinned, a colour that immediately places her in an unusual category. Her position as a doctoress situates her far higher in a house’s hierarchy than we might expect. There would be darker skinned slaves on Cherville’s plantation who are confined to working in the fields and bear the brunt of the ill treatment meted out, whereas those slaves considered lighter skinned might get to work in the household. Traditionally house slaves were thought to be higher in status than field workers, but whereas field workers get to leave the crops and spend time with their families in the village in he evenings, house slaves are at the beck and call of their master or mistress and even sleep in the house away from their families. They’re also closer to the male family members and therefore very vulnerable. There is a moment where Margaret is startled when she bumps into Hester on the landing, lurking in the darkness. She would only expect to meet servants of her own status on the master’s floor, not a black woman with her herbs and potions. I wondered how light skinned Willa was, to make her ‘palatable’ to Rowland Cherville, who appears to think slaves are expendable. He certainly doesn’t want them taking ‘his’ money.

Reparations are a huge theme in the novel and potentially the cause of Gervaise Cherville’s illness, as he admits the concerns and guilt around his treatment of slaves. Could his disturbing symptoms of insomnia, hallucinations and sleepwalking be put down to the end stage syphillis he’s suffering, or are the women he’s wronged in that house haunting him? When Hester first finds a dark, cold room off the kitchen she feels straight away that this isn’t a cold larder. There’s something about the space that she can feel and isn’t remotely surprised that slaves were sleeping in there, deemed unfit to be housed in the attic rooms with the servants. If all he wants to do is make reparations and apologise would it help the women to hear it? Or will the mention of their former master be so terrifying it disturbs their lives and leads to them fleeing once again? I suspected Gervaise hadn’t told Hester all that transpired between him and the women, in fact I doubted he even fully understood the extent of what he’d done. Yet it was Rowland Cherville who made my blood run cold, not only is he entering into exploitative relationships with young women who work in his factory but he doesn’t appear to have any empathy at all. His entire focus is on his own needs. He refers to his father’s money as his own, even though his father is still alive, and seems to have no feeling for his illness or imminent death. In fact he’d rather his father died, before he’s able to give all his money away. He also cares nothing for any of the slaves on whose backs the factory, Tall Trees and his inheritance have been built. They’re simply incidental to his own plans.

I really enjoyed the way this novel took me into the reality of Victorian England for black women. It gave me a new perspective, after Lianne’s first novel which looked at the rise of freak shows and the display of black women’s bodies. The private showings being another insidious and secret experience like rich men using women as domestic slaves and the objects of their desire behind closed doors, while seeming like a respectable businessman to society. Yet, the freak shows seemed to be freer and more in the control of the individual performer. One of the things I hated most when I visited the Slavery Museum in Liverpool, was the taking away of identity, so the way Cherville gave his slaves the names of goddesses made me shiver. It shows his desire for them on one hand, while keeping them in a cupboard, locked away all night like animals. While Hester is searching for them I was wondering whether they’d found their identity again, reclaimed their names and found a space to be relatively free. I feared that they’d had to adopt yet another identity, to disappear, constantly looking over their shoulder. Hester is a heroine that it’s easy to become involved with and I really sympathised with her feeling of being in-between: torn between being a wife and a sister; between her patient and her fellow women; not a servant, but not entirely free either. There’s even a revelation that draws her further into the history of Tall Trees. I wanted a happy ending for Hester, that she might be able to leave London and live that simpler life she and Jos have been craving. This is another triumph for Lianne Dillsworth and neatly places her on the list of authors whose books I would buy without question in future.

Published on 16th May 2024 from Random House

Meet the Author

Lianne Dillsworth lives and works in London. She has always loved anything and everything to do with books and her earliest memories involve reading and being read to. At school Lianne’s favourite subjects were English and History, so when she started writing, historical fiction was a natural choice. In Theatre of Marvels, her debut novel, Lianne indulges her love for the Victorian period evoking London in all its mid-nineteenth century glory. She is currently working on her second book under the watchful eye of her tiny terrier.