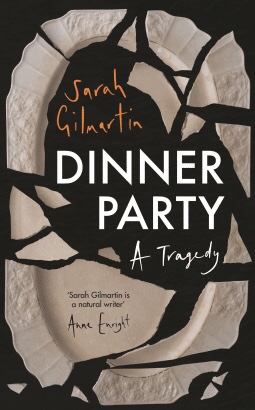

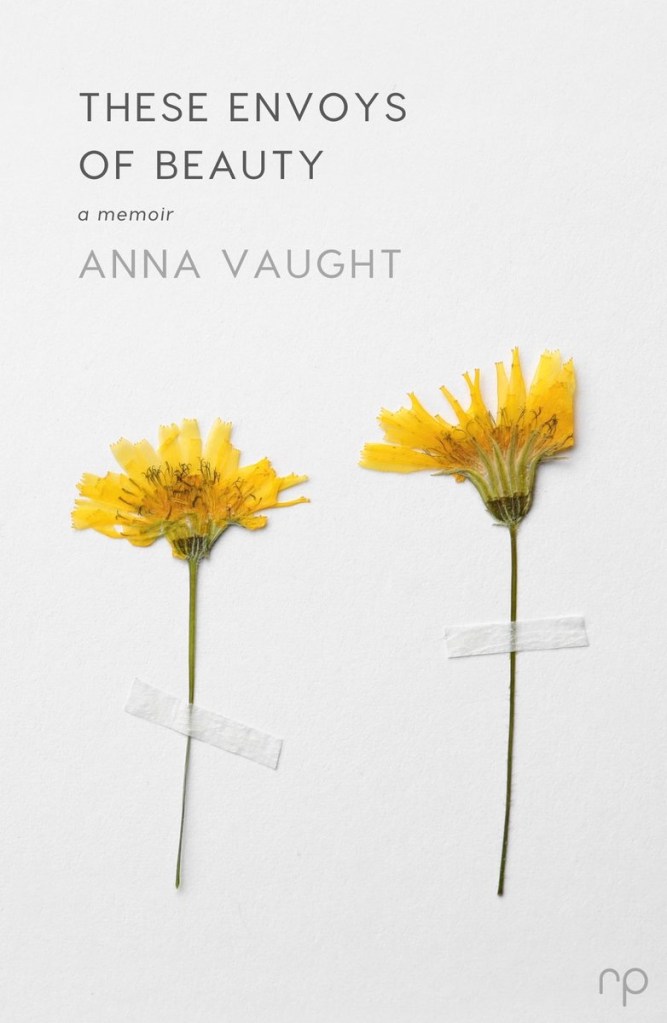

It was only yesterday on the blog that I was welcoming spring by talking about a book of poetry aimed at helping people with their mental health. Nature was one of the main ways we could boost our well-being, so it seems very fitting that I was also reading this beautiful memoir by Anna Vaught where she shares her very personal mental health journey and how nature became her best coping mechanism from a very young age. The book is made up of a series of essays, each one beginning with a quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Nature including the book’s title.

If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore; and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God which had been shown! But every night come out these envoys of beauty and light the universe with their admonishing smile.

Ralph Waldo Emerson. From Nature, Chapter One.

His words bring a sense of wonder to the natural world, and if kept and nurtured, that sense of almost childlike wonder is an amazing antidote to the hurried and stressful way of life we now have. In fact if we still have that ability to stop and be with the natural world around us, it becomes a time out of time. We come out of those moments and back to reality amazed at how much time has passed and how everything else in life receded and allowed us that enjoyment. As some of my bookish friends know, I have recently been struggling with my mood due to the frustration of having a multiple sclerosis relapse. While I am in pain and battling fatigue, my very busy brain is desperate to carry on writing my book. Basically my body can’t keep up with the breadth of my imagination and the desire to put it down on paper. Yesterday, we drove to our local farm shop and on the way home we passed a field that’s had a winter crop harvested and is only just growing a short covering of grass. From a distance away I suddenly saw two young hares – my favourite animal – chasing each other, weaving and winding around each other at speed then every so often stopping to stand on their hind legs and attempt to box. We pulled over and for a short while we lost ourselves watching these mystical creatures performing the rituals of their ancestors. My partner commented on how my face lit up while watching them, possibly because one of my earliest memories involves a leveret found by my dad that I was able to hold in my palm. I remember the softness of it’s fur, the cartilage of it’s ears and the way the light shone through the pink inside of the ear to show blood vessels coursing their way through.

Like Anna Vaught’s family we were rural working class, with my father either a farm labour or working in land drainage – a very important role in Lincolnshire where the 14th Century system of dykes designed by Vermuyden still keeps the county’s land drained for farming. As children, my brother and I would leave the house in the morning and not return till late afternoon. Vaught’s description of her childhood reminded me of those days where we would lie and read in trees, suck the nectar from sweet nettle flowers and watch the wildlife. I was obsessed with the Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady, so while my brother was fishing I’d do botanical sketches of foxgloves, campions and cow parsley. These countryside hours feel idyllic, but the truth was my mum struggled with untreated depression till I was a teenager. Since then my brother and I have both had our own bouts of depression, but thanks to better treatments and to my training in mental health I had the skills to know what was happening and ask for help. I have also developed my own toolbox for days when my mental health and physical health are having a battle with each other. Like the author, spending time in nature is definitely a large part of that. I truly bonded with this incredible, honest and moving book and was profoundly moved by the author’s decision to share her more painful life experiences. This is partly why my response is also very personal.

The author bases each chapter on a plan, such as Rosebay Willowherb or lichen and moss. She writes about the wonder of each living thing, but it’s also a kicking off point for her own memories and feelings at the time. She writes a deeply moving section in the first chapter where she admits that she was reciting the Latin names of plants in her head to calm herself and try to get to sleep. She told many different adults – the dinner lady, the teacher, the vicar – that she felt compelled to say them out loud ‘so as not to make the dreadful thing happen’ possibly the emergence of OCD. These little glimpses of the child Anna show how lost and unsafe she felt with her parents:

If, as a child you are surrounded by a sort of passionate morbidity, by a frightening psychiatric incident in the family – which is frightening because it is spoken of behind closed doors and euphemism – it may be that you need to latch on to things around you which provide stability and reassurance. Much of this was in the natural world for me.

P26

Vaught is open, raw and deeply moving in the sections where she writes about her childhood experience and it is worth mentioning that the book contains childhood mental illness, emotional abuse, suicide, depression and anxiety. She places her own warning for these subjects at the beginning of the book so I felt they were worth mentioning here. It is emotionally devastating to read someone crying out for help, but receiving nothing from the people expected to care for her most. She describes feeling dissociated, cut off from the world and the people in it as if she was living behind a sheet of glass. She writes quite bluntly that her parents did not talk about it or try to help her. Her mother’s view was the depressed people were indulging themselves. Teenage moods and PMS were imaginary and people who professed to be mentally I’ll had ‘failed to control themselves.’ I felt this in my core. To be so dismissed and gaslighted to this extent in your own family must be devastating to self – esteem and leaves you questioning and testing yourself permanently. She writes that she felt, not just unwanted, but a malevolent creature that might easily do someone harm, an idea that meant making friends and keeping relationships with extended family was quite difficult. It was also instilled in her that it wasn’t just her mum, that other family members and visiting friends had notice she was different too. Her father was distant, but when she was allowed to go out with him she felt chosen and would chatter away to him, probably making up for lost time, until he would snap and tell her to be quiet. On one occasion telling her that they preferred to spend their time with their ‘Number One Son because he listens and likes to be with us, and he never says a word. And you should know you are here under sufferance.’ How crushing must it have been to hear that, especially with her mother so angry with her, something she can only say now after years of therapy.

However, this is far from a misery memoir. I would say it is a story of resilience, of finding the things that boost it and removing from your life those things that crush your spirit. She provides possible mindful exercises that might calm and lists the places she finds most inspiring to visit and experience nature. She signposts the reader to other books that might give you coping mechanisms, while being mindful there is no one size fits all approach because we are all very different. One thing that caught my eye was something I have taught to my groups with chronic ill health and pain; that even in the depths of depression we must be mindful without our bodies and our emotions. We must observe how depression is making us feel both physically and emotionally. What is it about the weeks leading up to this bout of illness that you notice? Were you under stress at work? Were there financial pressures? Were you worried about someone else in your life? Then also make notes on what you did during the worst weeks that made you feel okay? Which strategies brought calm when your mind was spiralling with anxiety? Which people were the best to have around and vice versa? So in this way, a bout of depression or mental ill health has taught us something – what are the best ways to live that might help boost our resilience in the future? As with illnesses like MS, M.E. and various types of chronic pain, stress does worsen symptoms. Using these personal strategies may not totally remove the mental or physical ill health, in fact we may live our lives in seasons ( I always know I will have a short relapse in spring and another in the autumn) but we can be resilient, we can keep in mind that despite being in the depths of winter we can always come out the other side. This is one of the main lessons that the author has always taken from nature, it’s ability to heal itself and come back in the spring. We have faith that at this time of year, plants will start pushing through and now the hellebores and snowdrops of late winter are giving way to tulips, daffodils and bluebells. We plant our brown, unpromising bulbs in the late autumn into cold soil with complete faith they will push through and bring us joy, just when the winter has seemed so long.

If you can cope with the internal winter of depression then depression can be your friend’.

P 117

Not that we would wish depression on anyone, but that it can be a learning experience. It can teach us how to manage the next time it recurs and realise that even a life with limits has richness. This is something I’ve taken on board while reading and it started me off writing a short journal piece about what my bouts of MS can teach me and again it’s resilience. That just as it’s sure to happen again, I can also be sure that it will pass. I can use it to rest, to read and scribble notes, perhaps even to read solely for pleasure. My relapses are simply my body’s winter. To finish I loved her reference to Wilson A. Bentley who lived in Vermont and gave a great deal of his life to studying snowflakes, a natural phenomenon that’s so transient, simply melting away as though it never existed. Bentley felt they were a reminder of how transient earthly beauty can be, but that rather than rendering his study of them pointless, it made it more special because:

‘In the ephemeral nature of phenomena, however, he also found comfort, because while the beauty of the snow was evanescent, like the seasons or the stars he saw in the evening sky, it would fade but always come again.’

Introduction, The Envoys of Beauty.

Meet the Author.

Anna Vaught is an English teacher, mentor and author of several books, including 2020’s Saving Lucia. She has also written a short story collection, Famished. She is currently a columnist for MsLexia and has written regularly for The Bookseller. Anna’s second short fiction collection Ravished was published by Reflex Press in 2022 and 2023 will see five books including this one published across Europe. She volunteers with young people and is founder of the Curae prize for writer-carers and edits it’s journal. She works alongside chronic illness and is a passionate campaigner for mental health provision. Anna is published by Reflex Press and is currently working on another novel.