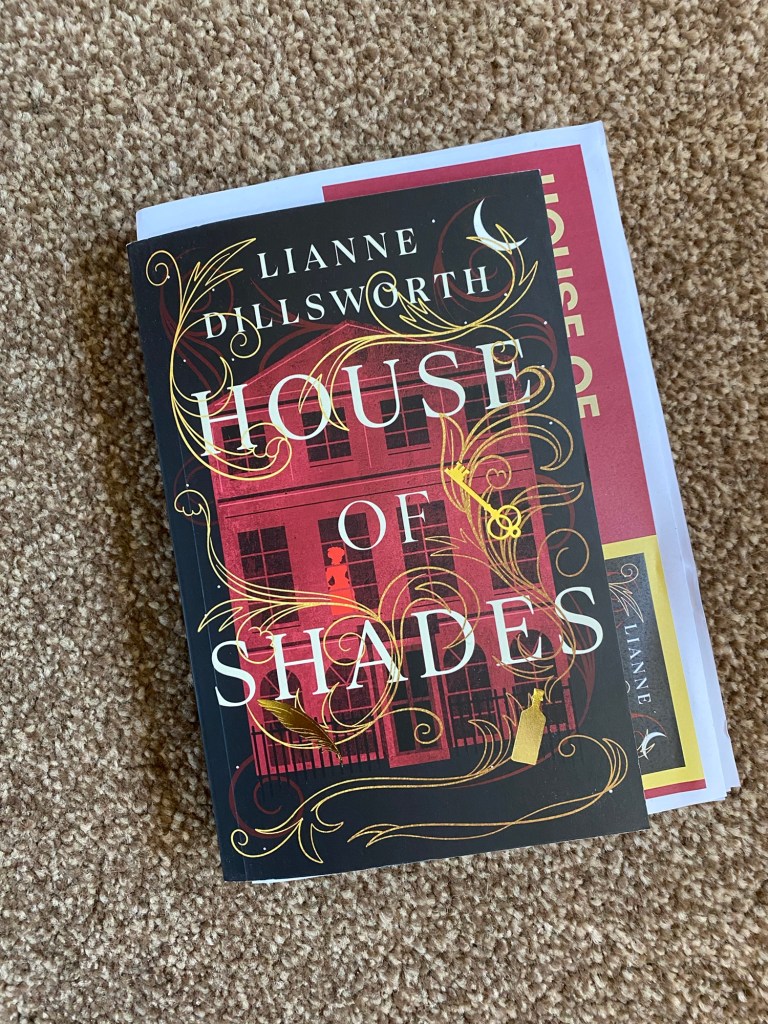

A shiver thrilled my spine at the thought of what might be contained in collections to be kept away from ordinary eyes…

London, 1873. Madeleine Brewster’s marriage to Dr Lucius Everley was meant to be the solution to her family’s sullied reputation. After all, Lucius is a well-respected collector of natural curiosities. His ‘Small Museum’ of bones and specimens in jars is his pride and joy, although firmly kept under lock and key. His sister Grace’s philanthropic work with fallen women is also highly laudable.

However, Maddie soon finds herself unwelcome in what is meant to be her new home. The more she learns about both Lucius and Grace, the more she suspects that unimaginable horrors lie behind their polished reputations.

Framed for a crime that would take her to the gallows and leave the Everleys free to continue their dark schemes, Maddie’s only hope is her friend Caroline. She will do anything to prove Maddie’s innocence before the trial reaches its fatal conclusion.

When choosing novels I have two favourite genres, historical and crime fiction. Author Jody Cooksley has combined the two in his compelling novel that was the winner of the Caledonia Novel Award. In Victorian London 1873, Madeleine Brewster, the daughter of a doctor, is courted by Dr. Lucius Everly a man seemingly intent on finding the missing link that will prove the evolutionary step between fish and mammals. He collects fossils and curiosities at his London home, hidden away in his ‘Small Museum’. His sister Grace undertakes work with fallen women at a house called The Evergreens which is held in high regard.

Madeleine accepts his proposal, imagining her life as a doctor’s wife will be similar to that of her mother and father. However, when she reaches her new home, life is very different to what she expected. She feels unwelcome in her new home, with housekeeper and gardener Mr and Mrs Barker seemingly in charge, keeping exactly the same routine from when Lucius’s father was alive. There is no space for her to organise or manage her own house and if it isn’t the Barkers, her sister-in-law Grace drops in unannounced and chooses the drapes or orders tea as if she is the mistress of the house, despite having her own. Having dreaded the wedding night, Lucius begs her forgiveness for his tiredness and departs to his own bedroom. Despite their reputations, Madeleine starts to suspect Lucius and Grace of unimaginable horrors. She hears a baby’s cry in the night, her husband arguing with his sister and items seem to appear and disappear from her room with alarming regularity. Despite trying to help her husband in his work and fitting in with the Barker’s schedule, Madeleine finds herself labelled as ‘nervous’ and then framed for the most terrible of crimes. A crime she did not commit. As she faces a trial Madeleine’s only hope is her friend Caroline, but can she prove her friend’s innocence before she is hanged?

This was an absolute cracker of a gothic mystery with a heroine who is in a terrible catch 22; either shut-up and be complicit in something horrific, or keep asking questions and be labelled mad by her in-laws. She is utterly powerless, but tries everything within her limited options to improve her situation. Madeleine is intelligent and no one could say she hasn’t tried in her marriage. When finally Lucius does come to her room it is a perfunctory act where she might as well have been an inanimate object. She tries to get used to these new couplings but there is certainly no love or even tenderness in it. The outcome is further tragedy for Madeleine and a means for Lucius to control her movements even further and an excuse for their nightly encounters to stop. Once physically recovered, she tries to use the only gift she has, her ability to draw in a style that would work for scientific illustrations. She is then let into Lucius’s small museum, a veritable treasure trove of nature’s oddities and anomalies, but also bleached bones of various different creatures that he hopes will prove his theory that fish developed into birds and mammals. He is gratified that Madeleine has a strong stomach, able to converse freely about the best ways of bleaching bone. He has lost many a servant girl who accidentally discovered the museum or his workshop where he prepares the animals whose bones he uses. They embark on a trip to Dorset together where he is showing his latest finds to his peers and Madeleine hopes they will enjoy combing the beach for fossils and she can do some more sketching. However, she has underestimated Lucius’s fanaticism about his theory and the terrible lengths he will go to in order to prove it.

The author brings all of these strands together beautifully, the glimpses into the past finally catching up with the present and Madeleine’s terrifying predicament. Will she be found guilty of infanticide? Caroline is desperately trying to uncover the truth and proves herself to be an incredibly loyal friend. I had so many questions as the book neared it’s end and the tension was riveting. Was Madeleine really seeing her sister Rebecca in the streets around Evergreens? Were items genuinely disappearing and appearing in her room? Was she sane or had she succumbed to mental illness? What were the noises in the house at night and can she really hear a baby crying? In fact the answers involved new maid Tizzy, a down to earth girl who’d had her baby at Evergreens and she provides an incredible light bulb moment! Everything around me disappeared (including the housework and cooking tea) as the first glimmer of truth came to light. I had to finish this book right now! I loved the elements of feminist thinking that were brought into the text including the use of Christina Rosetti’s poem ‘Goblin Market’ which tells of men who will take away and ruin any young maiden who isn’t on her guard:

‘Dear you should not stay so late, Twilight is not good for maidens; Should not loiter in the glen In the haunts of goblin men.

‘Goblin Market’,Christina Rosetti, 1862

Rossetti worked as a volunteer in a religious house helping ‘fallen women’ for eleven years, women like Tizzy and Madeleine’s sister Rebecca. Although Rebecca is seen as the fallen woman by respectable people, Madeleine realises that her own marriage simply gives her a mask of respectability. It does not mean they are happy, in fact it disguises what is truly going on behind closed doors. She knows it would take irrefutable evidence to save her and this is why she is in utter despair during her trial. She can’t imagine anyone breaking through that polite veneer of respectability to help her, because they risk their own reputation. Yet she needs someone respectable to vouch for her because housemaids and fallen women hold no power. Caroline is a liminal person in this respect, she is accepted in society as the daughter and wife of doctors, but her father and Ambrose are psychiatrists, dismissed as ‘mind benders’ by Lucius and this sets them apart. They’re respectable enough to be believed, but not so restricted by their standing in society that they daren’t speak up. Caroline is well aware of how powerless women are and the fates that can befall them. When she first sees marks on Madeleine’s wrists she knows she’s seen them before, on Ambrose’s recovering patients; ‘they were women too’. I loved Madeleine’s relationship with Tizzy too, they clicked immediately and talked with a freedom Madeleine’s never had before. She is her one friend in a house where the wife’s place is to keep quiet and only appear when necessary. All in all, this is a really well written and researched novel with all the ingredients I love in an historical novel: a fantastic sense of time and place; strong female characters that break through the Victorian ‘Angel in the House’ stereotype; those Gothic elements to bring a sense of mystery. Then added to this are the addictive twists and turns of a crime novel. What an incredible debut this is!

Out now from Allison and Busby.

Meet the Author

Jody Cooksley is an author represented by literary agent Charlotte Seymour at Johnson & Alcock.

In 2023 she won the Caledonia Novel Award with The Small Museum, a chilling Victorian thriller that’s due for publication with Allison&Busby in May 2024. Sequel to follow in 2025.

Previous novels include award-nominated The Glass House, a fictional account of Victorian pioneer photographer, Julia Margaret Cameron (Cinnamon Press, 2020), and How to Keep Well in Wartime (Cinnamon Press, 2022)

She is currently working hard on her next novel, another Victorian gothic set by The Thames. She has previously published essays, short stories and flash fiction.

Jody works in communications and lives in Surrey with her husband, two sons, two forest cats and a dangerous mountain of books.