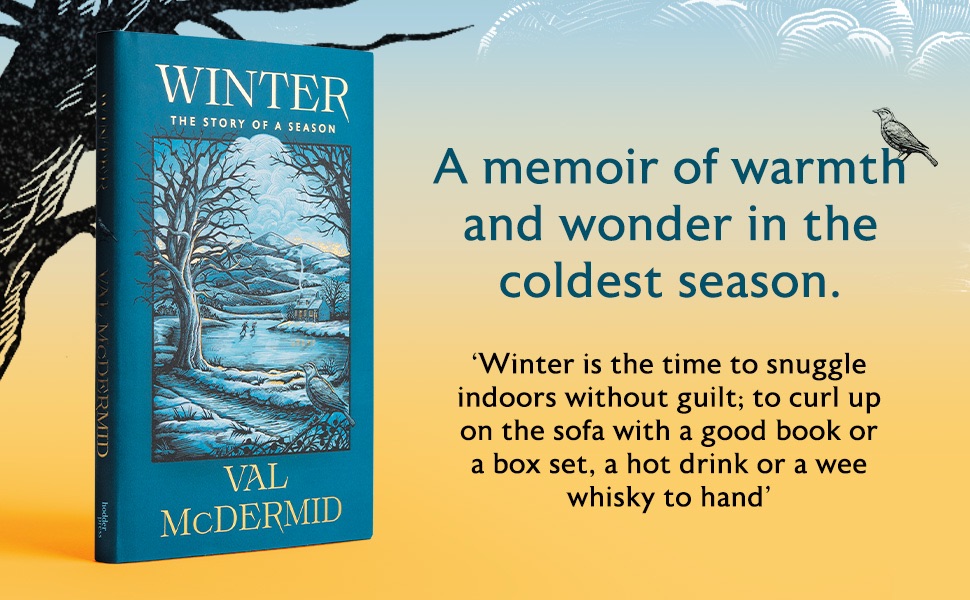

Winter is the time to snuggle indoors without guilt; to curl up on the sofa with a good book or a box set, a hot drink or a wee whisky to hand.

Val McDermid has always had a soft spot for winter: the bitter clarity of a crisp cold day, the vivid skies over the Firth of Forth, the crunch of frost on fallen leaves and the chance to be enveloped in big jumpers and thick socks.

In Winter, she takes us on an adventure through the season, from the frosty streets of Edinburgh to the windblown Scottish coast, from Bonfire Night and Christmas to Burns Night and Up Helly Aa. She remembers winters from childhood, the thrill of whizzing over a frozen lake on skates, carving a ‘neep’ (swede) for Halloween and being taken to see her first real Christmas tree in the town square, lights twinkling bravely in the dark Scottish winter night.

I was really interested to read Val McDermid’s Winter because I feel like it’s such a maligned season and it’s one that I enjoy. I’m a big fan of cozying up by the log burner with a mug of tea and a great book or film. I love crisp mornings where your cheeks feel pinched and seeing your own breath is still a novelty. I find myself able to do more in Winter, because somehow I feel invigorated by the cooler weather. I love winter festivals like Bonfire Night and a proper long Christmas – the full twelve days. It was joyous to find someone else who is able to enjoy winter in the same way I do and this book is definitely a celebration of the season I hear a lot of moans and groans about. Using creative non-fiction Val takes us through her favourite elements of winter in Scotland touching on nature, local customs and the memories they bring, as well as the comfort of resting and enjoying winter food.

The narrative was personal and very intimate too, like a stroll with a wise and knowledgable friend. There’s also a forthrightness in her character that I relished. One of my favourite things was her idea of being in step with the season because it’s an important part of how I live my life. I think we are part of an earth that has its rhythms and tides so it’s better for our wellbeing if we live with what our season and body tells us to. This season tells us to eat hearty stews and soups. It tells us to hibernate like bears – nights in watching films with a fire and sofa blankets. It tells us to gather with friends and celebrate light shining in the darkness. Whether we celebrate Hanukkah, the winter solstice, Christmas, Diwali or enjoy a good burn up on Bonfire Night it’s about lighting up the darker months and staving off the melancholy that can come in winter. Val tells us about Scottish traditions of carving turnips at Halloween and the incredible sight of the Norse festival Up Helly Aa which takes place across several islands in January, culminating in the Lerwick torch lit procession which is a real spectacle. I felt nostalgic for a time when the twelve days of Yule were just that and concluded with Twelfth Night festivities where the Lord of Misrule takes charge for a few hours. It was this and the Orkney Christmas Day tradition of The Ba’ that remind me of an old tradition called the Haxey Hood that at least three generations of my family participated in. It takes place on January 6th every year in the small village of Haxey in the Isle of Axholme. There is a Lord of Misrule and a Lady who drops her leather hood so two competing teams can play a long, arduous game to return it. The two teams have to get it back to whichever village pub they play for and it can carry on till nightfall. It’s best described as a cross between rugby and tug of war and results in a few hundred sweaty and muddy men either celebrating or commiserating in the pub.

My dad’s days of playing are over now but I loved that it elongated Christmas into January and I still keep to that tradition – in fact I can get quite grumpy when people ask me how my Christmas was when it’s Boxing Day! Or when I see people on Facebook who have their tree back in the loft on the 27th December. I spend the whole week saying ‘it’s still Christmas!’ I also get annoyed when people announce a diet on New Year’s Day! What a ridiculous idea it is to diet when our bodies are naturally telling us to eat as if we’re hibernating and there’s a mountain of Christmas food left to eat. Spring is the obvious time for renewal and rebirth, the perfect time to start new resolutions. We should be slower instead of wishing our lives away. We should stop and listen to what the season and our bodies are telling us, instead of being regulated by what’s in the supermarket. I found myself having these dialogues with the author in my head and I can easily see how I’d use the book as prompts for writing therapy. She tells us about Mardi Gras in New Orleans, a February festival, and it reminded me of the carnival and a particular February week in Venice when it unexpectedly snowed. It was magical and there was an excitement in the air as soon as we woke up. Someone had built a snowman outside with olive tree branches for arms and we walked to Florian, the famous cafe on St Mark’s Square and had a very indulgent afternoon tea and a hot chocolate that was thick, silky and warmed me to my boots.

It’s impossible to read or write a review of this beautiful little book without it conjuring up memories of your own. The illustrations are beautiful too and complement the writing perfectly. It felt like sharing winter memories with a friend and Val’s love of puffins has further cemented her place at my fantasy dinner party. The narrative rambles but it works, perfectly echoing her plea for a steadier and quieter pace of life in this season. Her writing style is lyrical and she draws you into something as simple as a winter walk, a skill I’ve always loved in her crime fiction. It’s perfect for keeping by the bed and dipping in and out of, rather like poetry. I was taken back to childhood and felt like I was given permission to claim this season for resting, relaxing and taking stock of- something I tend to do in that odd week of ‘betwixtmas’. I believe that the more we can go with the natural world rather than allowing the media, retail industry and other people to set our rhythms, then the healthier we’ll be mentally. Celebrate this season, relish its festivals and that Scandinavian hygge that we all read about a few years ago. If we accept this season for what it is, instead of wishing it was something else then we’ll be a lot happier. If you’re looking for a last minute Christmas present for a reader in your life then this is the perfect option.

Meet the Author

Val McDermid is a number one bestseller whose novels have been translated into more than forty languages, and have sold over eighteen million copies. She has won many awards internationally, including the CWA Gold Dagger for best crime novel of the year and the LA Times Book of the Year Award. She was inducted into the ITV3 Crime Thriller Awards Hall of Fame in 2009, was the recipient of the CWA Cartier Diamond Dagger in 2010 and received the Lambda Literary Foundation Pioneer Award in 2011. In 2016, Val received the Outstanding Contribution to Crime Fiction Award at the Theakstons Old Peculier Crime Writing Festival and in 2017 received the DIVA Literary Prize for Crime, and was elected a Fellow of both the Royal Society of Literature and the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Val has served as a judge for the Women’s Prize for Fiction and the Man Booker Prize, and was Chair of the Wellcome Book Prize in 2017. She is the recipient of six honorary doctorates and is an Honorary Fellow of St Hilda’s College, Oxford. She writes full-time and divides her time between Edinburgh and East Neuk of Fife.