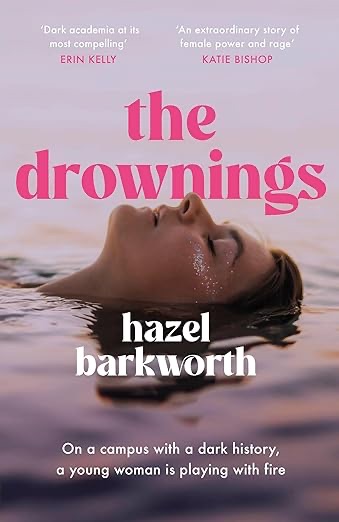

This is a fascinating read from Hazel Barkworth, capturing so much about the times we’re in while also exploring themes of identity, obsession, use of social media and modern day witch-hunts. Serena was born to swim. Her body is honed by years of training to be the best. When she thinks about her body, she imagines it sleek and pointed like an arrow shooting through the water. Her trainer Nico thinks she can go as far as the Olympics and within the family her winning streak makes her the centre of attention. Then one day it all goes wrong, because despite her training, focus and visualising the win, she loses. She can’t fathom why or what went wrong, but to add to her shock she then slips in the changing area and damages her knee. Now she’s on crutches and cannot swim at all. She knows she will not be ready to meet the next Olympics and the disappointment is crushing. Even worse, within her family, attention shifts to her cousin Zara. Zara has always had issues with her body image, but started an Instagram account promoting body positivity. Her curated Insta in shades of peach, teal and gold, is gathering momentum. She is blossoming in her success and has enough followers for companies to start sending her free products in the hope she might promote them. Just as Zara is making peace with her body and finding success, Serena has no idea who she is. With most of her time previously taken up with diet, exercise, warm-ups and time-splits, she doesn’t recognise herself. Her body only had one purpose and now it’s let her down. How can she be Serena, when the Serena she knew doesn’t even exist any more?

Serena decides to take up a place at university, at Leysham Hall, where her cousin already has a place. Here they both fall under the spell of their feminist lecturer in history, Jane. Serena meets her entirely by accident when walking the grounds one night. She sees a young woman poised by the edge of the river, that rushes downstream at this point of the campus. There have been warnings about this stretch of water, young women going missing and discussions about lighting the area always come to nothing. When the girl disappears, Serena rushes forward to help her. There is no hesitation when she realises the girl isn’t a strong swimmer and is in serious trouble. She leaps in and then Jane appears, just in time to help Serena bring the girl up to the surface and out. She doesn’t notice much about her that night, but she does end up in Jane’s history tutorial group and from that point on she feels drawn to the academic. It’s not a sexual attraction, she doesn’t want to be with her, it’s more that she wants to be like her. She loves the unfussy but stylish way that Jane dresses. She admires the knowledge and passion she has about her subject. Totally at odds with her dress sense, Jane’s tutorial room is a riot of colour turning the functional and boring space into something cozy and colourful. There are so many mementoes of places she’s been, feminist posters, colourful rugs and cushions. Mostly, I felt Serena is drawn to the fact that Jane seems so entirely sure of who she is.

A few of my reads this year have touched on a couple of very specific themes and when I thought about why, I could see that this is a product of the times we’re in. There’s the theme of witches and the witch hunting of the 17th Century which grew rife due to the obsession of James I /James VI of Scotland. The second was the influence and power gained by becoming part of all-male, elite, private school gangs like the Bullingdon Club, a club in which David Cameron, Boris Johnson and George Osborne were all members. The club carried out ‘pranks’ such as trashing the restaurant they met in and simply fixing the problem with family money. They burned ten and twenty pound notes in front of homeless people. I also believe this club may have been the source of the Infamous David Cameron and pig story. At Serena’s college it’s the Carnforth Club, named after their school founder they are robed from head to foot to keep their identities secret. As far as witches go, the words witch-hunt are being co-opted by men in powerful positions who don’t like it when their actions have consequences. We have seen it in the aftermath of the #MeToo movement, where men who are finally facing courts of law after years of abuse and sexual assault allegations, are claiming they are victims. The most recent is Russel Brand who has used his YouTube channel to protest his innocence, but has the tried to rehabilitate himself by becoming ‘born again’ and hiding within the Trump family, of all places. These and other men like Prince Andrew. Kevin Spacey, Jeffrey Epstein and Harvey Weinstein have all used the excuse that the media want to take them down. However, it’s not a witch-hunt when you’re one of the most privileged demographics of the world. If you’re moaning about witch-hunts you must genuinely be a victim and since most of these men are always punching down, I think we’re being gaslit.

The original witch-hunts were brutal and targeted mainly women. Jane tells them that witch trials took place where they now study and in fact, the place where Serena had jumped in to rescue a student was where witches were ducked. After a brutal interrogation that included torture, coercion and violation, suspected witches were taken to a river and ‘ducked’. If they drowned they were innocent but if they lived they were declared a witch and burned alive. Jane places this within a feminist framework. We know that ‘witches’ were usually women who lived alone, earned their own living from medical and herbal knowledge, often helped deliver babies in their area and helped other women. By offering advice on things like fertility, preventing pregnancy and helping girls in trouble, local ‘wise women’ gave the women around them some control and autonomy when it came to their own bodies. A woman like his is a threat to men and to the teachings of the established church. No wonder James I worked to the edict from Exodus ‘ thou shalt not suffer a witch to live’. Working as a counsellor and in chronic pain management for years I often realise I have quite a few friends who might come under suspicion from the witch finders.

Both Serena and Zara are dazzled by Jane, Serena has even wondered if Jane and Zara may be attracted to each other. Using Zara’s quite considerable social media platform, they encourage young women in the college to speak out about any sexist and misogynistic treatment they’ve suffered there, particularly if linked to the Carnforth Club. They are soon inundated with messages alleging everything from online abuse to sexual assault. Their anger comes to a head one night at a rally where both Zara and Jane will speak to any of the students who will turn up. Round a campfire they start to share their stories, with the evening rounded off with a call to arms. They must campaign for change. At the crucial moment, Zara is expecting the megaphone to be passed over, but instead Jane chooses to hand it to Serena. Fired up by the atmosphere Serena dives in and starts to rally the women and she is inspired. The night ends as Serena starts to lead a ritualistic dance and before she knows it she’s the leader, whipping up the women into a frenzy as they take off their clothes and follow her. Next day Serena is a little bemused at what happened, but it felt right at the time and she went with it. Even as she goes to sleep, someone is sharing a photograph of her naked and marching in the light from the campfire. It’s sent to the whole college. In the aftermath, Jane wants them to keep up the momentum and break into the hall, where a portrait of the college founder and instigator of the Carnforth Club has pride of place. While most of the group are happy to break in and cause mischief, Jane is considering something much darker and more dangerous. Will everyone go along with her plan? Since the rally, Serena has noticed that Zara is not herself. She seems to have lost some of her audience and her confidence seems to be following. Now that Serena is finding herself, it seems that Zara is losing herself.

The tension really builds here as the author takes us into final third of this thriller and I was fascinated to see how it turned out. I felt for Serena who seems to have found confidence and a sense of what kind of woman she wants to be, but is it real? She struck me as one of those children who’ve been pushed into specialising too early in life with no back-up plan. In all those dark, early mornings at the pool and the times she had to say no to social occasions to train, there’s someone who isn’t allowed to explore who she is and what she enjoys. Her time is so limited and she doesn’t form any meaningful friendships either. How do we know what we love in life if we’ve never tried anything else? She also has a very distant relationship with her own body that’s merely an athletic instrument. She’s used to ignoring aches and pains, divorcing her mind from how far she’s pushing her growing body and never seeing her it as a source of pleasure. Then suddenly she’s surplus to requirements and has no other plan. Placed into the chaos of fresher’s week and meeting so many different and strong characters must be bewildering. When people ask about herself, who is she? She struck me as a borderline personality, who takes on the issues and characteristics of whoever she’s with. She’s vulnerable, used to obeying authority figures and having them control everything down to her food. Zara seems equally fragile though, growing up in the shadow of a cousin who might go to the Olympics is not easy. She’s so proud of her influencer award and in a way, her Insta has been as much about her own validation and acceptance of her body, as it has about inspiring others. Once her star begins to fade, Zara’s confidence plummets and she becomes desperate to make her mark. The author shows us how fragile today’s young women can be with misogyny seemingly rife and the added pressure of a global audience on social media. I wasn’t sure how far either of these girls might go to impress their tutor and display who they are. That’s if this is who they are? This was a brilliant contemporary thriller that asks serious questions about how the authentic self forms within this confusing and dangerous world.

Published 1st August by Review.

Meet the Author

Hazel grew up in Stirlingshire and North Yorkshire before studying English at Oxford. She then moved to London where she spent her days working as a cultural consultant, and her nights dancing in a pop band at glam rock clubs. Hazel is a graduate of both the Oxford University MSt in Creative Writing and the Curtis Brown Creative Novel-Writing course. She now works in Oxford, where she lives with her partner. Heatstroke was her first novel and The Drownings is her second.