When 18-year-old Christian Shaw is found dead in an Edinburgh park, the city reels – and the shock only deepens when police charge her best friends, Eliza Lawson and Isobel Smyth, with her murder.

As social media explodes and headlines scream for justice, rumours of bullying spiral into something darker: whispers of rituals, obsession, and a teenage pact gone wrong.

Matthew Phillips, a respected heart surgeon, is called for jury duty on the case. But as the trial unfolds – and the girls reveal a chilling defence no one saw coming – he begins to question everything: the motives, the evidence, even his own judgement.

Who’s telling the truth? Who can be trusted?

And what really happened to Christian Shaw?

Let the Witch Trial begin . . .

I finished this book and had to give my head a little shake wondering what I’d just read. Harriet’s one of those writers where I end up devouring the book in a couple of sittings and then wish I’d taken my time because it’s come to an end! This grabs you from the very start as we follow Matthew, an esteemed heart surgeon, for jury duty. He is without question the perfect juror – intelligent, used to making life and death decisions and level headed. However, due to his job he could have easily been excused from jury duty so why does he stay? His colleagues seem incredibly annoyed that he has disappeared and is uncontactable for the foreseeable, because it turns out this is a complex murder case. Although Matthew seems an upstanding character he does seem remarkably keen on having a murder case and with this one he’s truly found the most intriguing. This is one of the most complicated and unlikely cases threaded with fanciful notions of devil worship and witchery. Matthew is our eyes so we view the case at the same time he does, as each witness takes the stand for cross examination. What they must prove is this point of Scottish law:

“Murder is constituted by any wilful act causing the destruction of life, whether wickedly intended to kill, or displaying such wicked recklessness as to imply a disposition depraved enough to be regardless of consequences.”

Put simply, the prosecution must prove that the defendants Isobel and Eliza knew that their friend Christian had a heart condition but were reckless enough to bully and fill her with such fear it killed her. Because of the immediacy of the narrative, the reader drinks in each gasp from the gallery and every revelation from the witness box, so much so that it was halfway through the book before I stopped to wonder how such a case could have made it’s way to court? Can someone deliberately frighten someone to death?

Matthew is observant, he has weighed up his fellow jurors and which ones might be trouble. He has checked out the defendants and wonders whether their appearance might prejudice the witnesses and jurors. Eliza is dressed well, whereas Isobel’s demeanour is surly and uncooperative. She looks down at the floor mostly and has a gothic appearance. She is being painted as the ringleader, but is she or are people being swayed by how she looks? The author adds small details that you barely notice at first such as Matthew’s own appearance. Fully suited and booted on his first few days, he is soon without a tie and then in jeans. His hygiene slips too and a rash starts to affect his hands, itching so badly during the evidence he struggles not to move. He drinks more and avoids his family, staying in his small apartment in the city. There’s also the strange journalist who catches his eye, then seems to disappear. One night she appears at his flat with a bottle and an ouija board, wishing to discuss the more gothic aspects of the case. The suggestion that the girls are practising witches is salacious enough to gain the headlines, but Matthew knows he shouldn’t be talking about the case at all. However, we as the reader are compelled to enjoy the suggestions of animal sacrifice, tarot cards and trying to summon the devil. It’s easy to forget that at the heart of this case are two young girls, who may have been unpleasant and even wicked but surely not criminal? We believe our narrator still, but should we? There are multiple layers to the books final chapters, something that this writer excels at. The occult elements are truly vivid and I found myself engrossed and even believing them in part. This is one of those books, where, like The Sixth Sense, you’ll be going back to see how you missed certain things. The final twists left me awe struck. This is a belting thriller, utterly addictive and compelling to the final page.

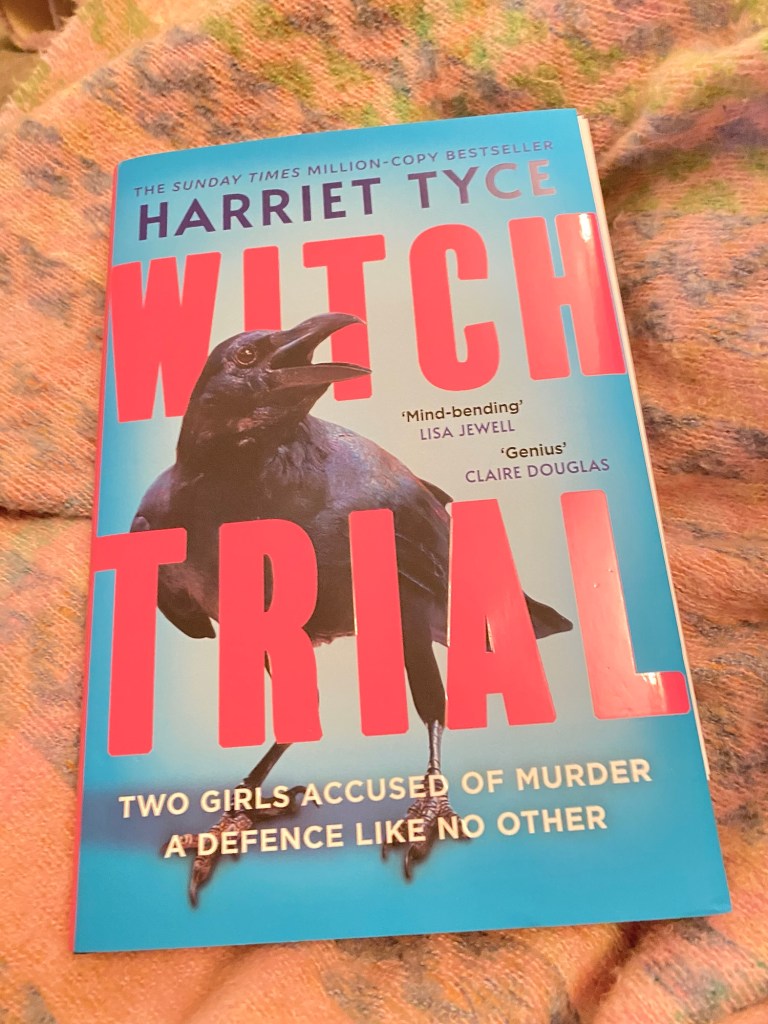

Out now from Wildfire Books

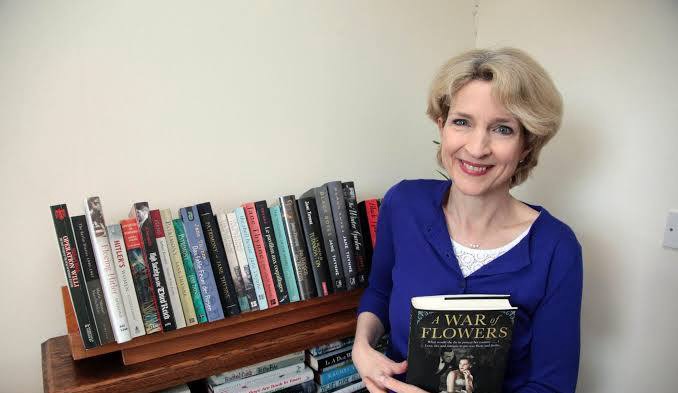

Meet the Author

Harriet Tyce was born and grew up in Edinburgh. She graduated from Oxford in 1994 with a degree in English Literature before gaining legal qualifications. She worked as a criminal barrister for ten years, leaving after having children. She completed an MA in Creative Writing – Crime Fiction at UEA where she wrote Blood Orange, the Sunday Times bestselling novel, winner of a gold Nielsen Bestseller Award in 2021. It was followed by The Lies You Told and It Ends At Midnight, both also Sunday Times bestsellers. A Lesson in Cruelty was published in 2022 and met with great critical acclaim and her fifth novel Witch Trial will be published on 26 February 2026. She is a contestant on series 4 of The Traitors. Follow Harriet on Instagram @harriet_tyce and find her Facebook page @harriettyceauthor.