Defending free expression has become a challenge. Words seem to matter more than ever and their impact. Just having an X account in the past week has been painful if you have empathy. It’s a battle for control where the desperate need to counter someone’s post, fights with common sense. By replying, even if it’s scathing, we have entered the arena and boosted that person’s profile. On the other side there are more people taking offence, on their own behalf and on the behalf of others. In this endless spiral of offence and discrimination it can be easy to become apathetic. It’s a political strategy the Kremlin has been using for years, bombard the people with so much opinion and disinformation that they become completely overwhelmed and withdraw. In this war of words, art is a form of activism, said the publisher Crystal Mahey-Morgan in an interview published online this week and as more books seemingly disappear from schools and libraries in America, we have to think carefully about the books we fight for. If we’re asserting that all books matter, then that applies equally to the books we like and those we don’t. If we’re saying books that offend others can’t be banned, we’re fighting equally for books we find distasteful or are offended by. There are books I rather not have read – there were definitely parts of American Psycho I could have done without, but I would never say they shouldn’t exist. Yet we seem to be stuck in a world where various groups in society want to ban or cancel books that don’t align with their views or misrepresent them. Even the writer’s behaviour, political views and private life can contribute to the moral panic around their work and our permission to read them. J.K. Rowling is a case in point and the controversy extends to her Robert Galbraith books which I still read. I grew up a long time before the internet and the cancel culture and I know that my ability to separate art from the artist is frowned upon. I want to talk to you about one of my favourite banned books and it’s the one people remember most – Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H.Lawrence.

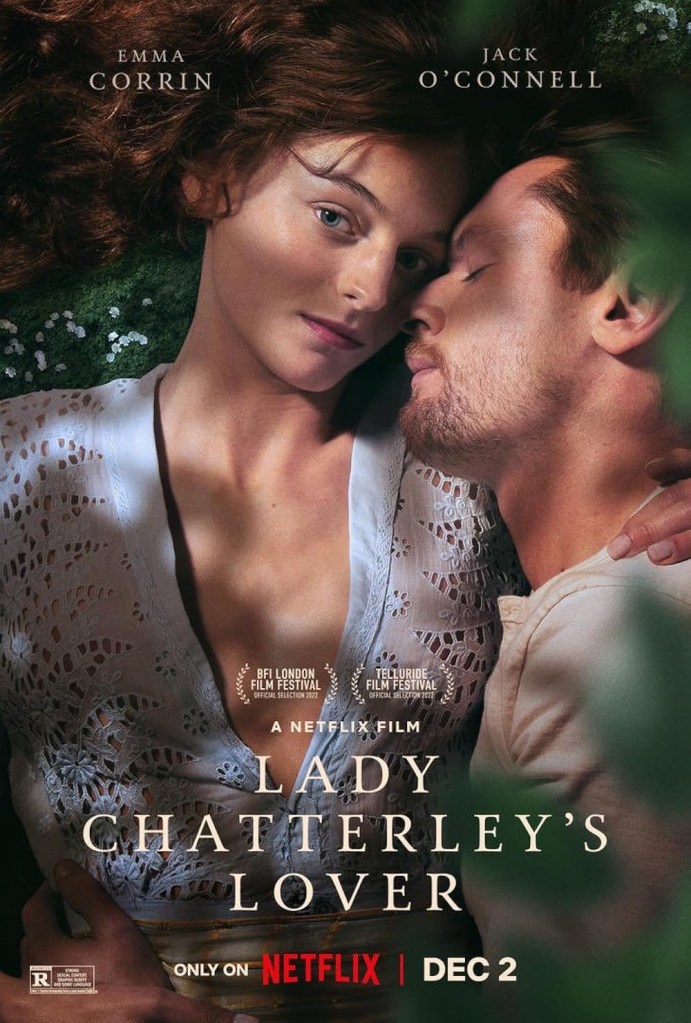

An adaptation of Lady Chatterley’s Lover has come to Netflix, where streamed shows are probably the 21st Century’s most popular creator of water cooler moments. The fact that this banned story is there for everyone to watch in their own homes would have shocked the 1960’s general public. The story is a simple one, about a young married woman (Connie Chatterly) and her husband’s gamekeeper (Oliver Mellors), and the forbidden love between them. First published privately in 1928, it took until 1959 for a ban on the book to be lifted in the U.S., and then 1960 when an uncensored version was published in the United Kingdom. Lawrence’s novel was also banned for obscenity in Canada, Australia, India, and Japan. People were genuinely shocked by the explicit descriptions of sex, use of four-letter words, and depiction of a relationship between an upper-class woman and a working-class man. To my mind, the most outrageous part of the book was the author’s portrayal of female sexual pleasure. In fact, Sean Bean’s ‘we came off together that time m’lady’ still lives rent free in my head. Maybe that’s because I spent most of the 1990’s dreaming, like the Vicar of Dibley, that Sean would come striding in and say ‘come on lass’ beckoning me with a single nod towards the door. I believed in him and Joely Richardson as those characters in the Ken Loach adaptation, more so than many others I’ve seen. Although I do have memory of going to see a more explicit French version of the book, wedged between a group of elderly ladies who gasped every time they saw a penis and a man who had a large bag of sweets that he would rummage in, very forcefully, at certain parts of the film. I moved seats in the interval.

Once I’d read the book, in my teens, I hated the way people talked about it. In my dad’s family, any mention was met with raised eyebrows and Monty Python’s ‘a nudge is as good as a wink’ type of humour. My mum loved D.H.Lawrence and I could see it bothered her to have him relegated to the role of pornographer. My dad’s brothers didn’t have a single bookshelf back in the 1970s and still don’t. They would come to our house with its massive bookshelves and ask ‘have you read them all? It was a question I never really understood. Did they think we were bluffing? Mum let me plunder her bookshelves all the time and this is why I know it isn’t just a ‘dirty book’. If I wanted to read something dirty I’d go for her Jackie Collins, Judith Krantz or Lace by Shirley Conran. I never reached for this as a prurient read, because it isn’t about sex. It’s about love.

“Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(Which was rather late for me) –

Between the end of the Chatterley ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.”

Wrote Larkin and perhaps that’s why my Uncles and Aunties raised their eyebrows, being teenagers pre-1960 and very unlikely to pick up a book by D.H. Lawrence. In fact once they’d seen the naked wrestling of the film adaptation Women in Love, they were convinced Lawrence was a pornographer. My mum happily shared these films with me as a teenager with no comment or explanation, she just let me make sense of it for myself and I knew there was something more complex at play here.

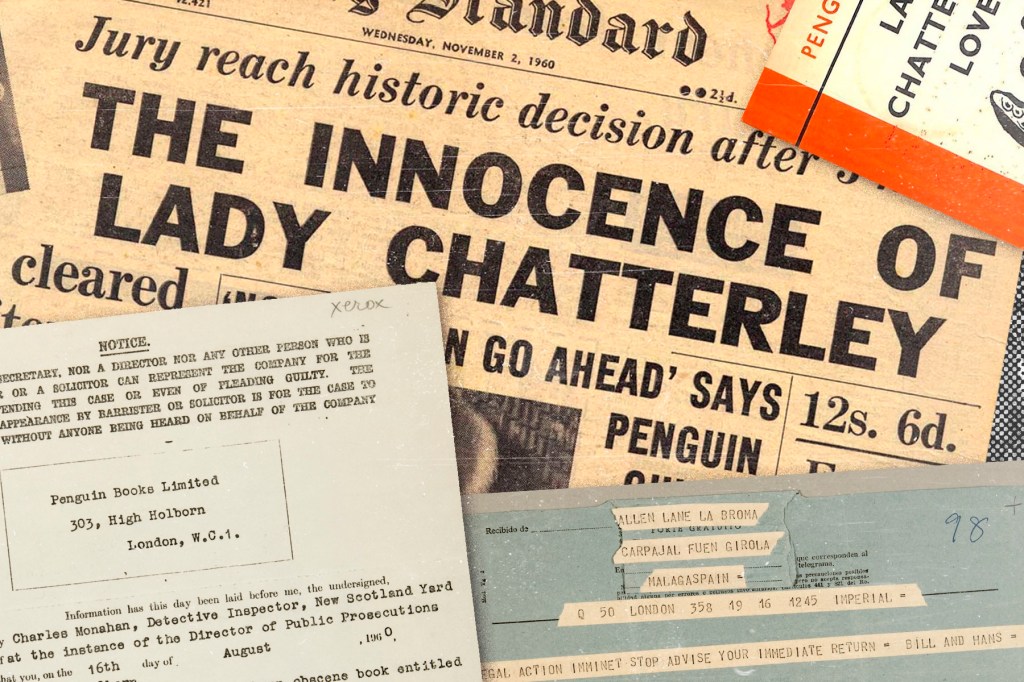

There is so much more to Lady Chatterley than the sex, although the sex is glorious and we’ll finish with that. Firstly it was fitting that when Penguin did publish in 1959 and challenged the previous year’s Obscene Publications Act, it was sold deliberately at a price that meant the working class and women could afford to buy it. Objections mainly came from the middle and upper classes, who weren’t necessarily concerned that Connie Chatterley committed adultery, but were objecting to her choice of lover. In fact it was this discrepancy between the classes that finally forced the court case, echoing the attitude of Clifford Chatterley. He was quite matter of fact about his wife taking a lover. He realised that his war injury would force Connie into a lifetime of celibacy and no chance of becoming a mother. He also wouldn’t have an heir. In one conversation he is quite open about the fact he doesn’t expect Connie’s fidelity, in fact he thought a lover might be the best thing for her. At least then they could have a child who would take on the title and estate. However, she was to choose someone from their class and he’d like to meet him. This turned Connie’s stomach for two reasons, she didn’t want to be passed from one Lord to another like a chattel and secondly she was shocked that Clifford didn’t seem to care. She’d expected there would still be some intimacy between them, even if it was confined to the care he needed. Yet, he chooses to employ a woman from the village who’s nursed during the war and there is something intimate in her care of him, something he gains some pleasure or comfort from. This leaves Connie free, but to do what. All their needs are taken care of by servants, she doesn’t need to work and while she does check in on tenants, they are isolated and she has few friends. She’s married and not married. She wants to find someone she has desire and feelings for, not just to jump in bed with someone of the right class and hope it scratches an itch. She wants true intimacy and she has that with Mellors. What we’re seeing in this affair is the breakdown of the aristocracy after WW1 and in this love story is the mixing of different social strata and the changing roles of women.

There’s also a massive shift for the working classes between the two World Wars. We see Clifford visit the colliery he owns and the workers are restless. They’ve been through terrible experiences on the battlefield and to come back and slot into their old social status, working under a man they’ve fought with in the trenches doesn’t sit right. They want better wages, better living standards and for the respect to work both ways. We can also see mechanisation creeping in. Clifford is ready to try anything new, whether it’s his new motorised bath chair or mechanising the pit. There’s an uncomfortable scene where Clifford uses his chair to walk with Connie in the grounds, but it becomes stuck in the mud. He angrily calls for Mellors to push the chair and he gamely tries to climb on the back and weigh it down enough for the wheels to grip. It’s a metaphor for the death of the aristocracy, all while Connie looks on awkwardly and Clifford becomes more and more frustrated.

Then there’s Connie and Mellors (Oliver) who are an interesting mix and their sexual tension is palpable but endearingly awkward at first. Mellors clearly desires her but doesn’t know how to treat a woman of her class. That’s not to say Mellors is stupid, because he isn’t. He’s self-taught and he reads too. Their conversations are on the same level as they get to know each other, but their dialect shows the huge difference socially and geographically. Connie has an openness that comes from being the daughter of an artist and it has always afforded her a huge amount of freedom. She and sister Hilda were expected to have lovers, to drive themselves around to parties and different stately homes. They have the opportunity to be upper class, particularly now that Connie is mistress of the Chatterley house, but are also eccentric and bohemian. They can use this to push the boundaries a little and Connie is encouraged to by her sister and her father when they visit near the beginning of the book, noticing she is pale, listless and a little depressed. They see the chasm that has opened up between husband and wife leaving them with the appearance of a marriage, but missing all the elements that make a marriage work – a shared humour, joint outlook, deep conversation and intimacy.

It’s no wonder that as Connie and Mellors think about a longer term relationship they know they’ll have to emigrate to somewhere new like the USA or Canada. These are the places where a relationship like theirs would be accepted. We see the incongruity of it in their early sex scenes where they move from intimacy to Mellors calling her m’lady because at the same time as being under him she will always be over him. There is tenderness between them, something more than sex. There’s real care and Mellors’s link to nature is important too, such as the first time they meet when he is placing pheasant chicks in their new enclosure. She sees a gentleness and a nurturing side that Clifford does not have. He would care if she was to be with another man and he wants to her to enjoy their encounters, not just him. When she does orgasm with him he comments on it and how special it is when that happens between a couple. He makes her feel safe. They have a joint childlike joy with nature, running around naked in the rain and threading wildflowers in each other’s pubic hair. He wants to be with her after the orgasm, which she hasn’t experienced before. I’m touched by this book and I’m infuriated that it was treated as pornography when it’s a comment on WW1, disability, masculinity, nature and so much more. It’s also a touching love story and you’ll root for this couple. They have an immediate connection, that goes beyond the boundaries of their class. They see each other as two equal human beings (an equality that Clifford disputes even exists) and recognise the loneliness in each other. Even if you do find the sex scenes awkward and you’ve never read this book due to its reputation, go give it a chance.

The political and religious climate in the USA has seen 16,000 book bans in public schools nationwide since 2021, a number not seen since the Red Scare McCarthy era of the 1950s. This censorship is being pushed by conservative groups of people, such as evangelical Christian and has spread to nearly every state. It targets books about race and racism or individuals of color and also books on LGBTQ+ topics as well those for older readers that have sexual references or discuss sexual violence. One of the most banned authors across America is Jodi Picoult with her novels Nineteen Minutes (school shootings), Small Great Things (Racism) and A Spark of Light (abortion). In the 2023-2024 school year, PEN America found more than 10,000 book bans affecting more than 4,000 unique titles. Here are a few of them:

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison and The Colour Purple by Alice Walker

Both these books are banned for themes of racism, sexual abuse and assault. Both break the silence around domestic violence and depict how tough life is for black women in the early 20th Century.

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood – the book that some people believe is coming to life before their eyes has themes of enslavement, sexual assault, misuse of religion and power. In a future where the elite class are unable to have children ‘handmaids’ are kept in the family home to provide the couple with children.

Call Me By Your Name by Andre Aciman – is a first love story that springs up between a teenager and an older man, cited for depictions of homosexuality

The Kite Runner by Khalid Hosseini – was put forward by a group of mums concerned about their children reading an account of ‘homosexual rape’ but Hosseini fought the ban with a letter that talked about the book’s insight into Afghan lives and inspired children to ‘desire to volunteer, learn more, be more tolerant of others, mend broken ties, muster the courage to do the right and just thing, no matter how difficult.’

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult – begins with a black midwife assigned to a woman in early labour who is then refused by the father, a white supremacist. When the baby is ill and there is only one midwife available does she touch the baby or wait for someone else? This really does have impact and made me think about my own privilege.

For more info on Banned Books Week visit ⬇️⬇️