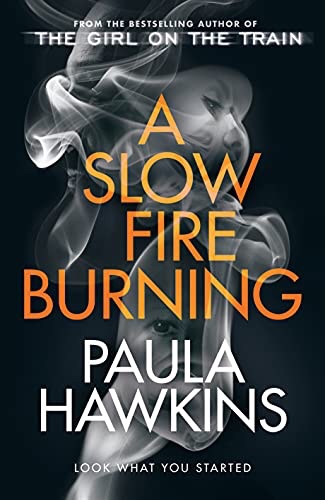

I’m a big fan of this author’s previous novels Into The Water and The Girl on the Train. Incidentally, I didn’t like the latter’s film relocation to upstate New York, because I didn’t feel it had the necessary grit of the book’s London location and lost something in translation. I’ve been looking forward to her new novel and I spent the weekend on my chaise longue reading it with a bar of Green and Blacks Sea Salt. Pure bliss! The novel is set in London, on a stretch of the Regent’s Canal between Bethnal Green and Islington. We open with a body being found on one of the canals, the deceased is a young man his neighbour only knows as Daniel. When she boards his boat and finds his body covered in blood she knows she must ring the police. However, in typical Hawkins fashion, the author wishes to unsettle the reader and leave them unsure of who to trust. So, although his neighbour Miriam looks like a run of the mill, middle aged and overweight woman, used to being ignored, she does something unexpected. She notices a key next to the body, and as it doesn’t belong to the boat she picks it up and pockets it.

Our other characters are members of Daniel’s family, who live within walking distance of each other in this area. Daniel’s mother Angela is an alcoholic, in a very strained relationship with her only child until his death. Then there’s his Aunty Carla and Uncle Theo who live near the boat. Daniel appears to have a closer relationship with his Aunty Carla, than he did with his mother, but is it really what it seems? Miriam has noticed some odd comings and goings from the boat next door. This is a family with secrets, both old ones and current ones. Miriam noticed that the girl who works in the local launderette, Laura, was with Daniel on the night in question and they had a row. Laura could have killed him, but Miriam doesn’t think so. Then there’s Irene, an elderly lady who lives next door to Angela and has also noticed some strange behaviour next door too. She knows the family well although Angela has often been too distracted by her own life to form a friendship. Irene does have a soft spot for Laura who helps her out from time to time, by going shopping or running errands. Like Miriam, Irene is also wondering if everything is what it seems with this murder. Lonely people observe a lot and although the family won’t realise this, she’s in possession of a lot of information. Something seismic happened to this family years before, something that changed the lives of everyone involved. Might that have a bearing on their current loss? Could that be the small flame, burning slowly for many years, before erupting into life and destroying everything?

I absolutely fell in love with Laura. She has a disability that affects her mobility and, along with many other symptoms, she has problems keeping her temper. Her hot-headed temperament has led to a list of dealings with the police. This isn’t her normal character though, this rage seems to come from the accident she had as a child. She was knocked down by a car on a country road while riding her bike and broke her legs, as well as sustaining a head injury which has affected her ability to regulate her emotions. Further psychological trauma was caused when she found out the man who hit her, was not just driving along a country round, but driving quickly away from an illicit encounter. Who told him to drive away and why? Laura feels very betrayed and now when she feels threatened, or let down, that rage bubbles to the surface. She’s her own worst enemy, unable to stop her mouth running away with her, even with the police. She has a heart of gold, but very light fingers. She’s shown deftly whipping a tote bag from the hallway of Angela’s house, but in the next moment trying to help Irene when she can’t get out. I found myself rooting for her, probably because she’s an underdog, like Miriam. Miriam feels that because of her age, looks and influence she is completely invisible. She has been passed over in life so many times, it’s become the norm. However, there is one thing she is still angry about. She wrote a memoir several years ago and showed it to a writer; she believes he stole her story for his next book and she can’t let that go.

I love how the author writes her characters and how we learn a little bit different about them, depending on who they’re interacting with. They’re all interlinked in some way, and their relationships become more complex with time. As with her huge hit The Girl on the Train, the author plays with our perceptions and biases. She doesn’t just plump for one unreliable narrator, every character is flawed in some way and every character is misunderstood. We see that Miriam is not the stereotypical middle-aged woman others might think she is, as soon as she pockets that piece of evidence at the crime scene. Others take longer to unmask themselves, but when they do there’s something strangely satisfying about it. We even slip into the past to deepen our understanding of this complicated group of people, letting us into all their dirty little secrets, even those of our victim Daniel. When I’m counselling, something I’m aware of is that I’m only hearing one person’s perspective of an event. Sometimes, that’s all it needs, some good listening skills and letting the client hear it themselves. Yet, it is only one part of a much bigger story. Occasionally, I do get an inkling of what the other person in the story might have felt and I might ask ‘do you think your wife heard it like that or like this?’ If I say ‘if my partner did or said what you did, I might feel….’ it makes the client think and asks that they communicate more in their relationship. Sometimes the intention behind what we say becomes lost in the telling. That’s how it was reading this book, because we do hear nearly every perspective on an event, but also how each event or interaction affects the others. The tension rises and it was another late night as I had to keep reading to the end. Paula Hawkins has become one of those authors whose book I would pre-order unseen, knowing I’m going to enjoy it. In my eyes this book cements her position as the Duchess of Domestic Noir.

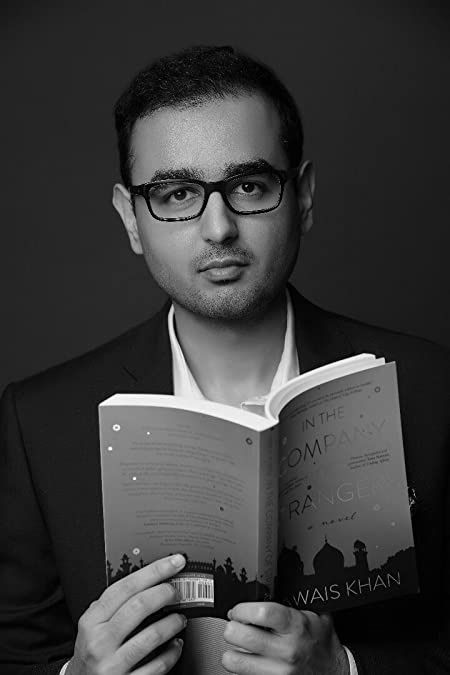

Meet The Author.

PAULA HAWKINS worked as a journalist for fifteen years before turning her hand to fiction. Born and brought up in Zimbabwe, Paula moved to London in 1989 and has lived there ever since. Her first thriller, The Girl on the Train, has been a global phenomenon, selling 23 million copies worldwide. Published in over forty languages, it has been a No.1 bestseller around the world and was a No.1 box office hit film starring Emily Blunt.

Into the Water, her second stand-alone thriller, has also been a global No.1 bestseller, spending twenty weeks in the Sunday Times hardback fiction Top 10 bestseller list, and six weeks at No.1.

A Slow Fire Burning was published on 31st August by Doubleday.